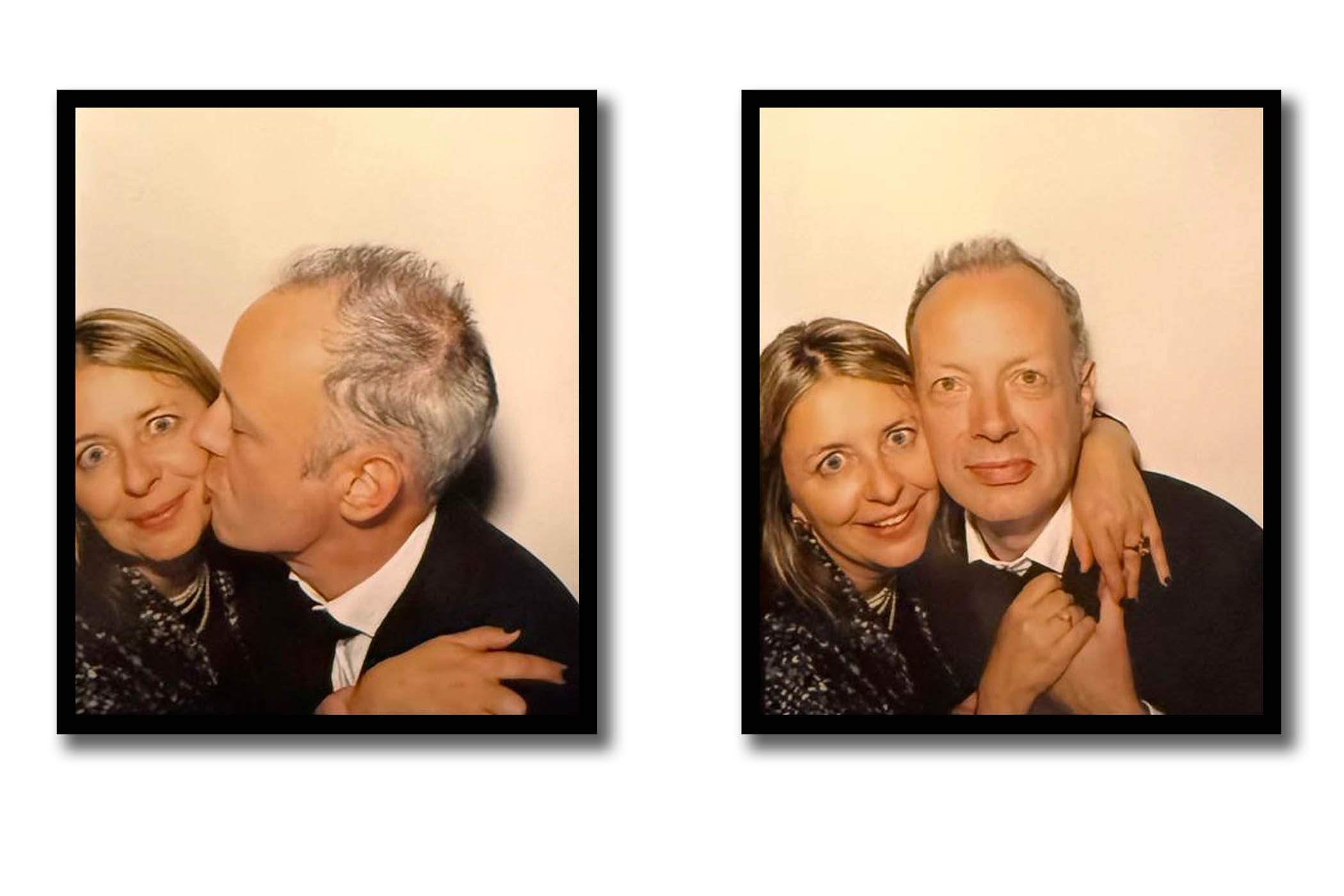

Rachel Cooke, my beloved wife, died as she had lived – valiantly. From the first diagnosis of ovarian cancer in April this year to the final days, she remained utterly herself: funny, gracious, beady, wry, outward-facing. Her endurance in these weeks and months of illness, in and out of hospital, was astonishing.

During the 19 years we were married, I had always admired her. But by the time she came to meet her fate, I was in awe of her. She had been through the ordeal of her life, in so much pain one couldn’t have been surprised if it had broken her spirit. It never did. She was forthright and unselfpitying to the last.

Character is destiny. We all know privileged and well-off people who are deeply unhappy and insecure. Contrariwise, there are those with little in the way of advantages to whom the month is ever May. Rachel took some time in becoming the person she was meant to be. She knew early on you could be two very different things at once.

As a Yorkshire lass, she was rooted in a world of no-nonsense, plain-spoken folk who wouldn’t stand for pretension. So she loved the earthy hospitality of her working-class grannies, relished lamb chop with chips and all the dainties of the family table. But the shy provincial teenager yearned for something else, and sensed that beauty had to play a central part in it – the beauty of art and books and music and clothes and talk.

At her comprehensive school in Sheffield she once came a cropper when a fancy dress contest was held. This being the mid-1980s, most of the kids came dressed as Phil Oakey or Madonna or some other pop star. Besotted with Brideshead, Rachel went as Sebastian Flyte, bearing a teddy and dressed in a blazer and cricket whites. Bad enough that none of the pupils had a clue who she was trying to impersonate. Sadly, none of the teachers did either.

She loved telling this story of how she provoked her uncouth peers to mockery, but it secretly pained me, as did the story of her being dropped from the school hockey team because she was “rubbish”: I couldn’t bear the thought of this sensitive bookish girl being humiliated.

Rachel outside a favourite restaurant

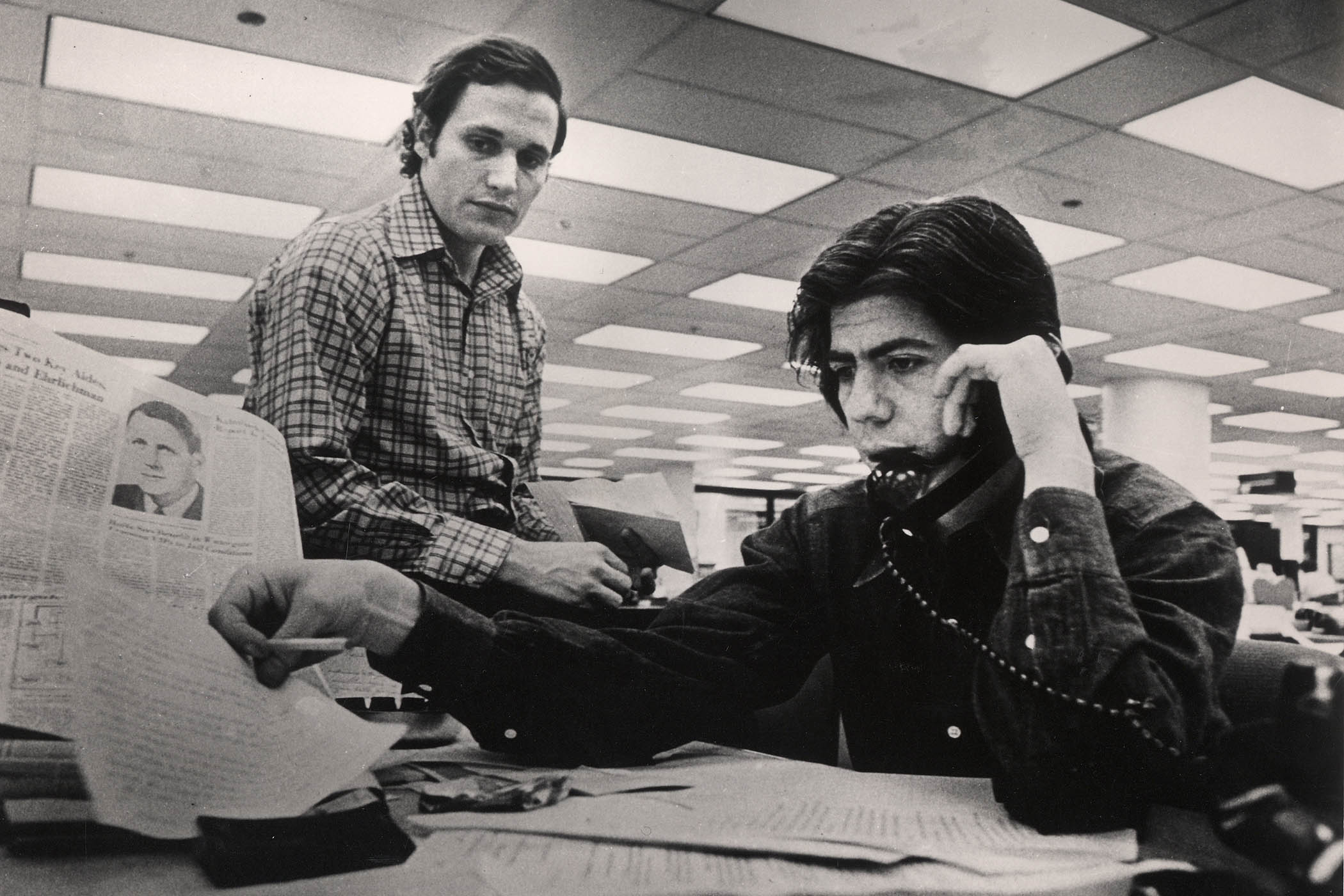

Yet the wound can also be a gift. She took on the armour of resilience, to survive not only her school days but the continuing bitterness of her parents’ separation (they split when she was six). She also began exploring the possibilities of a future career. Aged nine, she was running her own newspaper, the Interest (not a bad title!). Aged 19, at Oxford, she was pursuing stories for the student newspaper Cherwell, later becoming its editor.

I’m not sure where the ambition sprang from, but I imagine her back then as a Rosalind Russell in denim dungarees, cracking jokes and haring off on her bicycle for the next scoop. In fact her idol was Katharine Whitehorn of The Observer: she was bewitched by her chic style and her apparent confidence in a world bossed by men. If Katharine could carry all before her in the 1950s and 60s, why shouldn’t Rachel do the same in the 1990s?

At the Sunday Times Style section, she was at first cowed by her editor, Jeremy Langmead, who sent her on a variety of outlandish stunt commissions, dressed up to attract the bewildered stares of the public. It would probably be called bullying today, but she gamely stuck to the brief, knowing what a story it could make. About a year after she left the paper, she was surprised to get a call from him, inviting her to dinner. Jeremy had missed having her around. He wouldn’t be the last. They went out, and became great friends – best friends, no less. He called her “me lovely Cookie”.

In May 2003 another journalist, Nicola Jeal, asked Rachel if she’d like to meet a pal of hers: film critic, Liverpudlian (“very close to his sister – that’s a good sign”). Introduced at a new Gordon Ramsay place in Knightsbridge, we got on swimmingly, and Nicola’s matchmaking earned her the unlikely title of “Fairy Godmother”. By this point, Rachel was already writing up a storm at The Observer – her sacred lodestar – and filed a column the next week referring to a “perfectly adorable man who confessed to me that he never ate vegetables apart from potatoes and green beans”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

An early teasing of my faddy eating habits … but, hey, how about perfectly adorable? Nobody had ever called me that before (or since). At our wedding in April 2006, she gave a speech that became so instantly celebrated among the guests that I would later refer to it, with only slight envy, as “Gettysburg”. I reread it yesterday. It’s short-ish, explosively funny, extremely tender, and surely the only wedding speech ever that makes allusion both to Spanx (popular undergarment of the day) and George Gissing. Bravo, my dear.

I reread her wedding speech yesterday – surely the only one to mention both Spanx and George Gissing

I reread her wedding speech yesterday – surely the only one to mention both Spanx and George Gissing

Whether it was a speech, or an interview, or an opinion piece, or one of the many hundreds of reviews she wrote, she was exacting on the matter of quality. “Your easy reading makes for damned hard writing,” Sheridan is supposed to have observed, and Rachel would never let a piece out of the house without having slaved over its composition. What is a writer’s style, in the end? Clearly, it’s to do with choice of words and the rhythm of sentences; also to do with tone.

But behind all that lies something else – call it the voice, harder to define but so vital to the effect. Voice is the element that seduces and beguiles and entertains. It forms that intimate communion between a writer and her readership, and it’s something that cannot be taught. This is the rare gift that Rachel possessed, the voice that takes you into her confidence and reassures you almost like a friend: a friend who’s witty and well mannered, but also rigorous and decisive. Readers loved her because they felt somehow understood by her. I lost count of the number of times out in public when strangers, shyly, or excitedly, would approach her: “Are you Rachel Cooke?” She professed to be embarrassed, but I never knew a writer who so enjoyed a compliment.

She would be at her desk by nine. She had already filleted the news from the Times with a cup of tea in bed and was ready for the day. She didn’t stop for lunch unless it was for a professional engagement, and got annoyed if some PR had dragged her away for nothing. Around two o’clock on a Monday, she would proudly say: “That’s my graphic novel column done. Just another four more pieces to write this week.”

We have already heard much about the variety of her output from Tim Adams’s superb tribute in last week’s paper. What continually struck me was the way she oscillated between high and low. She could be as compelling on Annie Ernaux as she was on Jilly Cooper. She loved Dame Janet Baker and Owner of a Lonely Heart by Yes. She was as happy to be watching the sweetly silly BBC comedy Here We Go as she was to be at the Barbican with her friend Catherine for an early church baroque concert.

She was peculiarly unsnobbish: the marvellous trick she pulled was to make you read her whatever the subject. Would I watch Shark! Celebrity Infested Waters? Please, God, no, but her New Statesman review of it furnished an unimprovable comic miniature: “When, in the first episode, a juvenile lemon shark nipped Ross Noble’s leg, I felt a sense of utmost solidarity. Go, fish!” I pick this at random from a thick sheaf of cuttings on her desk and note that they all date from this year, when she was writing under a possible death sentence – yet still making her readers laugh.

Rachel having returned from hospital on 29 October this year

I don’t want to idealise her. She could be sharp-tongued and blithely outspoken. Because she held herself to high standards, she demanded them in others. I tried hard not to displease her, and if I ever did, I’d get what I called the “mongoose stare”, her blue eyes suddenly arctic with disapproval. She had an especial aversion to male pomposity (it was nearly always male) and made great sport of it in consequence.

One of her earliest pieces for The Observer’s food magazine was an encounter with the TV chef Rick Stein. Having made the five-hour trip from London to Padstow, she was outraged at not being given a scrap to eat, and mentioned this in her piece. Stein flew into a rage on reading it and told her editor she was “banned” from Padstow. Rachel pondered how this ruling might be implemented: “Would there be road blocks? Would my photograph be pinned, convict-style, to the walls of his restaurant? It didn’t seem worth going all the way back to Padstow to find out.”

She didn’t mind tangling with the big beasts. One night two years ago we were at a memorial tribute to the writer Jonathan Raban (she had once been babysitter for Raban’s brother’s children in Sheffield). A Senior Novelist we knew and liked was delivering his address and happened to make slighting reference to The Observer books pages, which he claimed had been in decline for years. “Rude,” said Rachel, quite loudly.

An hour later, we were in a Marylebone pasta joint when the Senior Novelist and his wife came in. Some moments went by, and he sidled over to our table to apologise for offending her. I sat there, silent as a cat, and lapped up the spectacle of this elder statesman of the British novel offering contrition, saying: “I’m so sorry” over and over to her. Eventually, I chipped in: “I think you’ve got to forgive him now,” and Rachel, warily appeased, sat back. “It wasn’t really an apology,” she remarked later. “He still said our books pages hadn’t been the same since Terry Kilmartin [who died in 1991].” But we had a good laugh about it.

And sometimes came genuine moments of reconciliation. Another novelist, less senior, responded on Twitter to her disobliging review of his latest book with a suggestion that she needed “a good seeing-to” (Let’s not get into the implications of that). Ill-feeling simmered for years, probably exacerbated by the fact they’d attended the same school in Sheffield, until one day they decided to make up and had lunch together. Phewissimo.

She had an especial aversion to male pomposity and made great sport of it

She had an especial aversion to male pomposity and made great sport of it

At the start of April, the results of a scan on her abdomen came back. She had thought (hoped) the pains that excruciated her were caused by the stress surrounding the Guardian’s defenestration of The Observer in late 2024. Instead, traces of cancer had been found on her ovaries. In my diary I wrote: “I sense her fear. But of course I believe she’ll survive it, and we’ll be fine. My optimism is without foundation but it is intense and immovable.” An hour after she had told me this, in tears, I found her on the couch in our living room hunched over her laptop, a study in concentration. She was a newspaperwoman, and she had a deadline to meet.

Her Stakhanovite work regime was maintained up to the point of her first admission to hospital in June, when her bowel was perforated from the effects of her chemotherapy. There followed a summer of dashes to A&E and long weeks at University College hospital (UCH) London, interspersed with joyous returns home, where she could banish the oppressive memory of hospital food.

When the chemo failed, her oncologist Michael Flynn switched her to the experimental treatment of immunotherapy – her last escape route. Disaster followed disaster. The drugs triggered in her a neural tumult, she had a terrifying seizure in front of me and was later transferred to the hospital for neurology in Queen Square in Bloomsbury.

For a while I feared her mind was lost. Her reaction was considered so vanishingly rare that she became a study of interest to Dr Aisling Carr, who asked permission of the patient to write a paper on it. “Sure,” replied Rachel, “so long as I can write about it for The Observer.” This was one among many projects she was storing up for the future. She wanted to write a book about the artist Tom Phillips, and another one about Margaret Thatcher. They will remain phantoms.

Life moves pretty fast. In March, we were walking around Windermere on a minibreak. In October, I was helping her walk from the bedroom to the bathroom. In the last weeks, I read to her in the evenings from Jenny Uglow’s lovely book A Year with Gilbert White, the 18th-century naturalist whose quiet, steady, civilised voice was hugely consoling to both of us.

Rachel at Windermere

Her appetite had fled and she was wasting away to spectral thinness. Her thick hair was reduced to a gamine crop. “My sparrow,” I called her. But her amazing smile was undimmed, and I would try anything to summon it. “I thought I’d have much more time,” she said. In a recent email, my friend Susanna Gross described Rachel to me as “the cleverest woman I know”. So very recent. Susanna, writer and editor, died the same week as her, of the same disease, at 58. Rachel was 56. The pity of it.

When reading or reviewing a biography, her principal interest would be in what new material it contained. Having published in 2013 Her Brilliant Career, a biographical study of 10 pioneering women of the 1950s, she was proud of how much original research had gone into it. She wanted books to tell her something she didn’t already know. So, in honour of that spirit, let me tell you something new about Rachel.

One evening at UCH, her close friend, the artist Claerwen James, confided in me that Rachel had just had a long talk with her about Catholicism. Huh? She had never mentioned this to me before. Claerwen, herself a convert, swore she hadn’t prompted the conversation, and I believed her. As the weeks dragged on and her time closed in, we talked around the subject, and I realised she was quite serious.

The night before she entered a hospice, I telephoned the parish priest of St Etheldreda’s in Clerkenwell, the church where we married in 2006, and asked him to come to the house. At her bedside, Father Anthony Furlong took her confession, gave her communion, and received her into the Catholic church. Later that evening, Rachel, my sister and I talked about it, moved by what had happened. I opened a bottle of champagne and we toasted the new convert.

Maybe this all sounds a bit …Graham Greene. Perhaps you feel bemused by the story; or even disappointed. I can only assure you that Rachel was determined on it. Why? She wouldn’t tell me, and that’s fine. Does anybody want to be entirely understood? Don’t we have to keep a little mystery about ourselves, for our own sake? Go on, please: misunderstand me.

On the morning she died, I got out of the bed that the hospice nurses had made up for me in the corner of her room. Her breathing had gone somewhat ragged. I had no clean T-shirt so I put on one of hers, with a quote from Joan Didion across the chest: “Writers are always selling somebody out.”

Rachel was fiercely inquisitive about the truth of things. She was a passionate arguer, not in the spirit of “I must have my say” but because she was stirred by an urge to learn. She was, truly and honestly, the most loving person I’ve ever known.

She was a writer to the tips of her fingers. But she never sold anybody out.

Photographs courtesy of the family