In 1987, I set off alone from Jiayuguan, the Great Wall of China’s far western outpost in the Gobi desert, aiming to become the first foreigner to make a journey on foot along the line of the Wall’s ruins. Along the way I extravagantly shot an entire 36-exposure roll of film, before spending more than an hour near the Wall’s seaside terminus of Shanhaiguan trying to get a spectacular shot for a book cover.

By then I knew I had a real story to tell. My 1987 in numbers would suffice to express the physical, political and romantic dramas of my life-changing year: 2,500km on foot over 78 days, nine arrests, one deportation, two passports and three marriage proposals to my now wife, Qi. Every day I’d hit the wall, physically exhausted. After nine increasingly serious run-ins with the police for trespass – and repeated trespass – in areas closed to foreigners, I knew what a perilously narrow line I was treading. I had hit a wall mentally too, and was almost out of film.

Yet on a late November morning at Mule Horse Pass in Hebei, I was inspired to take another self-timer photo. It turned out to be my most important Wall photograph of all.

Snow had blanketed the landscape overnight, making the scene too good to miss. I groped in the deep snow for some loose bricks and stacked them high to improvise a stand for my Olympus OM-2. Peering through the viewfinder, I raised the lens barrel a tad with the lens cap. Nudging the springer mechanism, the buzz began. I had 12 seconds on the self-timer to get just beyond my spot, turn around, and try to look unperturbed by the danger as I strode, head up, eyes open, arms swinging, towards my camera. I was petrified at the thought of slipping flat on my back, sliding down the Wall and plummeting off into the bush and rubble several metres below.

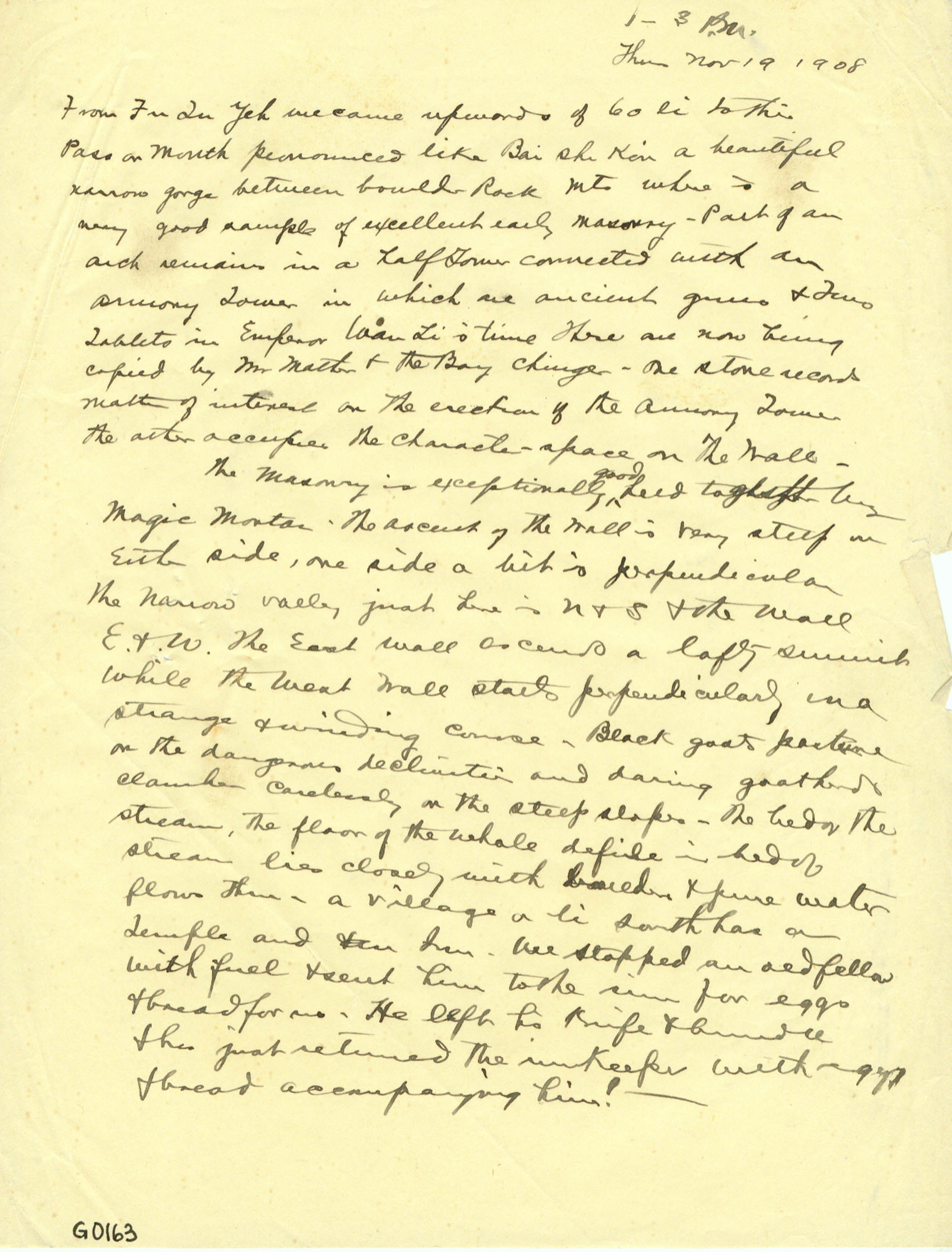

William Geil walked the length of the Great Wall in 1908

Miraculously, the photo turned out to be a one-shot wonder. It paved my way to a remarkable meeting. When my book was published, a woman called Marjorie Hessell-Tiltman heard me on a radio interview and wrote to me. “I have another book, The Great Wall of China, written by an American, William Geil,” she wrote. “It contains more than 100 impressive photographs. Perhaps it’s too late to be of use, but I would gladly give it to you.”

Until I received the book, I had believed, in Great Wall terms, that I was the only William the Conqueror. But Geil had seen it from end to end, almost 80 years before me. I now had to accept that I was in fact William the second.

I opened the book at a photographic plate; Geil sat in the foreground of the photo, just as if he’d been waiting to introduce himself to me. I vaguely recognised the location, thinking of the snow shot, so I reached for my own book. It was the same place – but clearly not quite the same. There was a glaring difference: during the intervening 79 years, a watchtower that stood behind Geil had become a mound of rubble. Geil had seen a much better condition Great Wall in 1908 than I’d seen in 1987. I was runner-up once more.

I ended up surpassing every foreigner’s temporary fascination with the Great Wall by returning to China to stay there permanently in 1990. By living and working in Beijing, 400km of Great Wall now lay within a 120km radius of my home. Exploring this outdoor museum in the mid-1990s marked a second phase of my exploration. Then in 1998 I moved even closer, by buying a farmhouse in a hamlet that gives access to the best 10km of its entire length: the Jiankou section, famed for its majesty and danger.

Related articles:

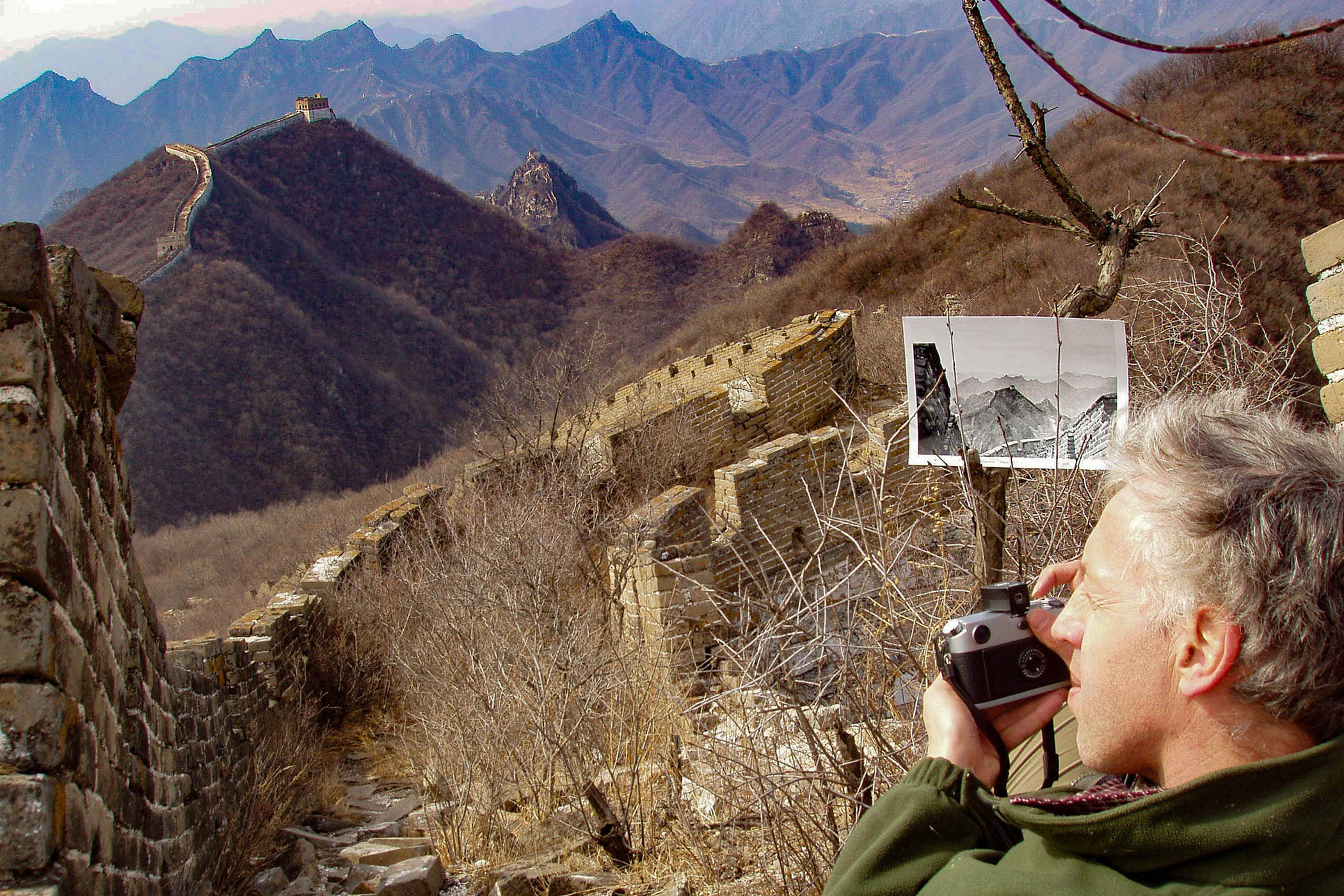

William Lindesay at a snowy Mule Horse Pass…

… and the picture that Lindesay found last year of Geil at the same place, with the watchtower still intact

With the Wall in my backyard, I assumed a guardianship role. I organised the first mass cleanups of litter on the Wall in 1998, placed “green message signage” and enlisted farmers to help keep the trails tidy. On the eve of the new millennium, I invited a few friends to a Wild Wall retreat near my new home. As we hiked towards the Great Wall, the future of the world’s largest building dominated my thoughts. The watchtowers on the skyline above me, which for centuries had served as lookout posts for soldiers guarding the frontier against nomadic attacks on horseback, were witnessing a new onslaught. With improved transport, many more people came and saw, dropped litter and scrawled graffiti. Their arrival prompted farmers to demolish their old farmhouses and embrace concrete in an attempt to cash in on tourism. The state had no mechanisms in hand – no laws, schemes, not even a vociferous spokesman – to defend the Wild Wall.

It was then that I realised how Geil and I might collaborate. I could scale up from that single photo taken at Mule Horse Pass by systematically searching for and rephotographing all the other Wall views in Geil’s book. We could then present a comparison between the Wall’s appearance in 1908, before it was ravaged by wars, revolutions and sociopolitical upheavals, and now. By evidencing a century of changes, I hoped that our state-of-the-Wall portfolio might inspire initiatives to stop it collapsing further, draw attention to the encroachment of development, and chivvy along the formulation of regulations to protect it from exploitation.

My task was to find about 60 spots along the 8,851km-long Ming Wall. One of my most poignant searches was for a view that Geil captioned: “The Picturesque Pass, a superb view of the Great Wall erected by Emperor Wanli.” It depicted a string of four perfectly preserved watchtowers positioned at equal distances along a high mountain ridge. From memory I surmised that the photograph was taken in Laiyuan County, Hebei, about 200km from Beijing.

One of Geil’s Great Wall letters

I headed to Chajianling village. As usual, I began by engaging a few locals to look at my scanned photos. “There are no such fine towers here,” an elder said. Was this another wild goose chase? Perhaps, but the only way I could eliminate the location was to walk the Wall on both sides of the village. As I beat my way through low bushes, glancing between the landscape and down at the photo, I began to realise that the locals might be wrong.

I reached precisely where Geil had stood in November 1908. It was here that Geil saw what he had called the Razed Towers Pass. I saw how picturesque it had once been. I steadied my emotions and took my photograph.

Geil and I were kindred spirits, both lured to the Wall by seeing it marked on maps. We both had conversations with locals who helped us comprehend that the English translation of the Chinese wanli changcheng to “the Great Wall” was off the mark; the figurative meaning – “the endless wall” – was a better measure of it. We also agreed on the place on the Wall’s route that best demonstrated its beauty: Geil praised “the most extracting views” of Thistle Ravine, a village beside Jiankou, where I’d settled. He had passed by my front door in June 1908. I began to wonder whether we were not two Williams, but one.

Eventually, my thoughts turned to the whereabouts of Geil’s original expedition records. After searching American museums and libraries, I was puzzled why Geil had seemingly been forgotten in his own country. Showcasing my photography alongside his exceeded my expectations: several exhibitions followed, as did the announcement of the first laws to protect the Wall. But I still longed to find Geil’s Great Wall archive, setting myself the challenge of doing so by 2008, the centenary of his journey.

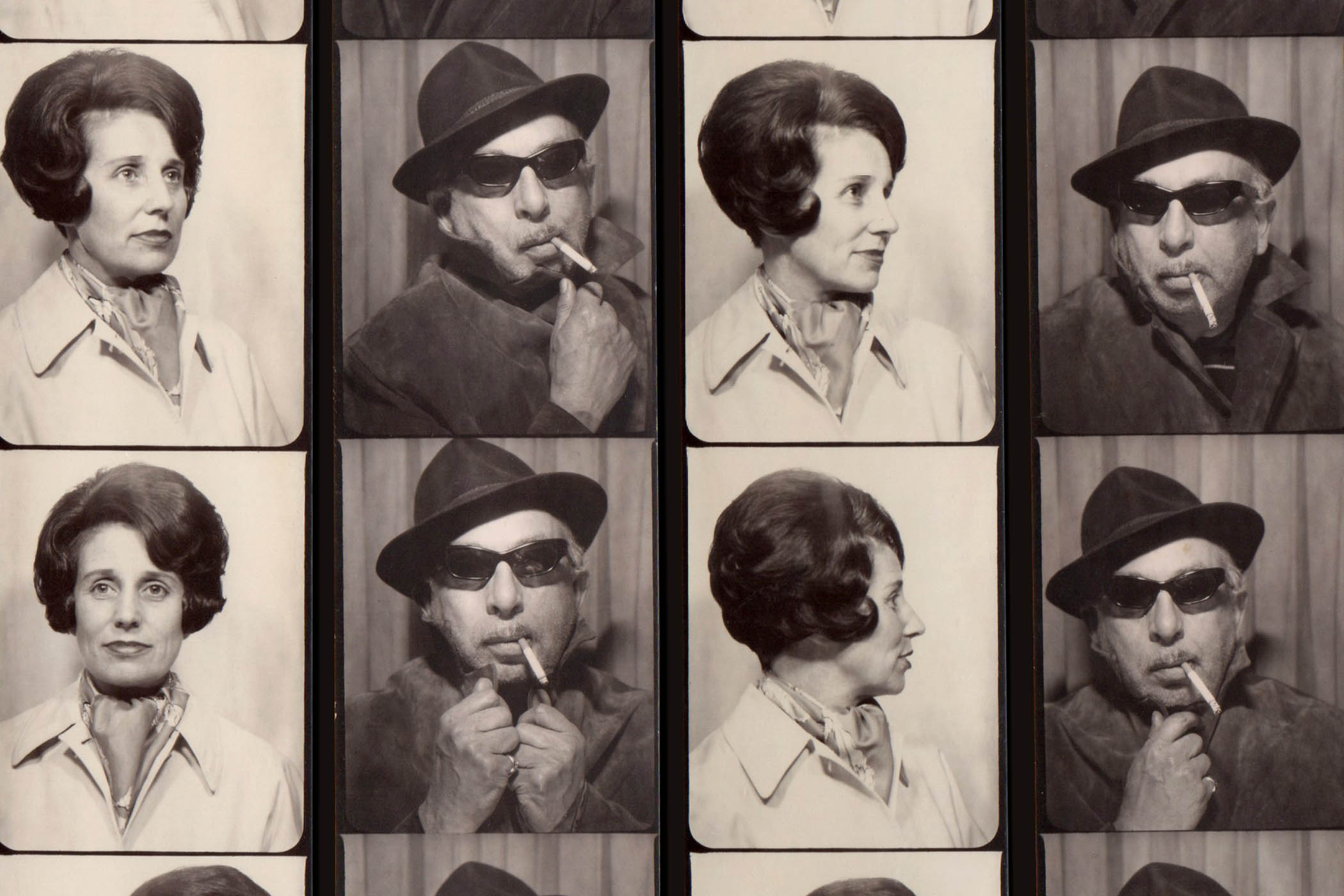

Geil used magic lantern slides from his trip when delivering presentations

I started by looking for Geil’s descendants in his hometown of Doylestown, Pennsylvania. He married Constance Emerson in 1912. Just 13 years later, Geil died from influenza while aboard a ship sailing from the Holy Land to Venice. Constance survived him until 1959. But what had happened to his archive? My first lead was in finding notice of a funeral in 2007 held for a Constance Geil Laycock, who was survived by three sons and a daughter. I knew I had to find one of them. But according to US census data, there were more than 1,600 Laycocks in the country. My search for Geil’s descendants began by sending hundreds of emails. Only a tiny number of recipients replied, none of whom were among those I was looking for. So I came up with a more feasible plan. I’d visit Doylestown in June 2008, pay my respects at Geil’s grave, and initiate a local search.

In February 2008 I received an email from a Robert Laycock who told me I’d found the right family, and they agreed to travel to Doylestown to meet me. A month later a volunteer at Doylestown Historical Society, Tim Adamsky, emailed me saying that some boxes of materials that belonged to Geil had been donated to them. The first one he delved into was crammed with papers mentioning the Great Wall. He had Googled “William Geil Great Wall” and found me.

My trip to Doylestown was overwhelming. A memorial gathering beside William Geil’s grave. A visit to his former mansion, which was adorned with tributes to the Great Wall. Meeting the Laycock brothers: Brad, John and Bob. And rummaging through boxes full of the explorer’s records: typed letters, pages from the first draft of his book, notebook jottings, newspaper clippings. These visits, meetings and finds were revelations but, disappointingly, there were hardly any images of the Great Wall. Where could they be?

As I beat my way through the low bushes, I began to realise that the locals might be wrong

As I beat my way through the low bushes, I began to realise that the locals might be wrong

Father John Laycock, one of the three brothers, clarified the family history. “My grandmother rarely spoke of her husband,” he told me. “His death, after only 13 years of marriage, remained an unhealed wound. As a child I explored every corner of my grandmother’s home, the Barrens in Doylestown, except [my grandfather’s] study. That door remained locked, until August 1959, when Grandma Geil died and the Barrens was left to my mother, Connie, who’d grown up knowing little or nothing about [William] the hidden explorer of the house.”

To ready the 34-room mansion for sale, an auction of its contents was held. According to records kept by the local auctioneer, Brown Brothers, the explorer’s possessions were sold off at $1 a box. One buyer appeared to have obtained all of the boxes. When that buyer died, his children sold off what they could and left the unsold papers to be donated to the Doylestown Historical Society. And so the explorer’s archive was disseminated. However, Father John recalled: “I entered [my grandfather’s] study for the first time that summer… the room was a dusty jumble of books, boxes, papers and mementoes of the explorer’s travels. I got just a few boxes and put everything into storage when I entered the church. I don’t recall seeing anything about the Great Wall. I do remember there was a walking stick.”

It seemed my search had reached a dead end. But at the beginning of 2025 – the centenary of Geil’s death – I realised that beyond it there would be no more major anniversaries of his journey in my lifetime. So I decided to return to Doylestown and see the Laycock brothers again. My visit was preceded by a procession of bad news. Father John Laycock had passed away. The owner of the Geil mansion had died and it had been sold. Doylestown Historical Society suffered an electrical fire in which Geil’s desk and typewriter were lost. But Bob Laycock informed me of some much-needed good news: they had found 22 boxes of Geil’s materials while clearing Father John’s basement and would delay looking inside them until my arrival. Could this be my long-awaited “tomb of Tutankhamun” moment?

The ‘cover shot’ from Lindesay’s 1987 expedition

In the boxes, at first we saw a lot of Africa. Then the Greek island of Patmos, where St John, imprisoned by the Romans, had his vision of the Apocalypse. And then the Holy Land. A book, Ocean and Isle. At last I saw some photographs of China, but of the Long River, about which Geil wrote the book A Yankee on the Yangtze.

When people see the Great Wall with their own eyes, whether it’s for the first or hundredth time, they often say with gusto: “There it is!” And this is what I yelled as I pulled the first Great Wall photograph from a box. From deeper inside came photographs showing a succession of views, both recognisable and unknown to me, one after another; and most amazingly, a view of my own Great Wall backyard, a spot just 3km from my home.

The haul also contained a cardboard box of negatives in their hundreds. A huge steel trunk (made by Jones Brothers of Wolverhampton) containing extra-large photographs by the score. A leather suitcase on which was painted: “This crossed Africa and China with Wm. Edgar Geil.” A wooden box containing 64 magic lantern slides, used by Geil when delivering illustrated presentations. Maps of the Great Wall’s provinces. Correspondence headed “The Great Wall Letters”, typed on the spot along the way, in the lee of the Wall. Draft chapters of his book The Great Wall of China.

This hoard was so much more than his book; it was the entire photographic and written record of William Geil’s journey along the Great Wall and back to Peking, as never before seen, so detailed it could be turned into a movie script.

Geil was a great admirer of those smart nuggets of Chinese wisdom, and every page in his Great Wall book is topped by a proverb. One that’s appropriate for what happened next is: “The apple does not fall far from the tree.” Bob and Brad donated all of their grandfather’s Great Wall archive to me, in my capacity as founder and director of International Friends of the Great Wall. Archiving, studying and exhibiting it will probably keep me occupied for the rest of my life. Once packed up, these artefacts from his journey were once again making their way across the world, going full circle from China to Doylestown and now back, to reside once again beside the Great Wall.

Photographs courtesy of William Lindesay