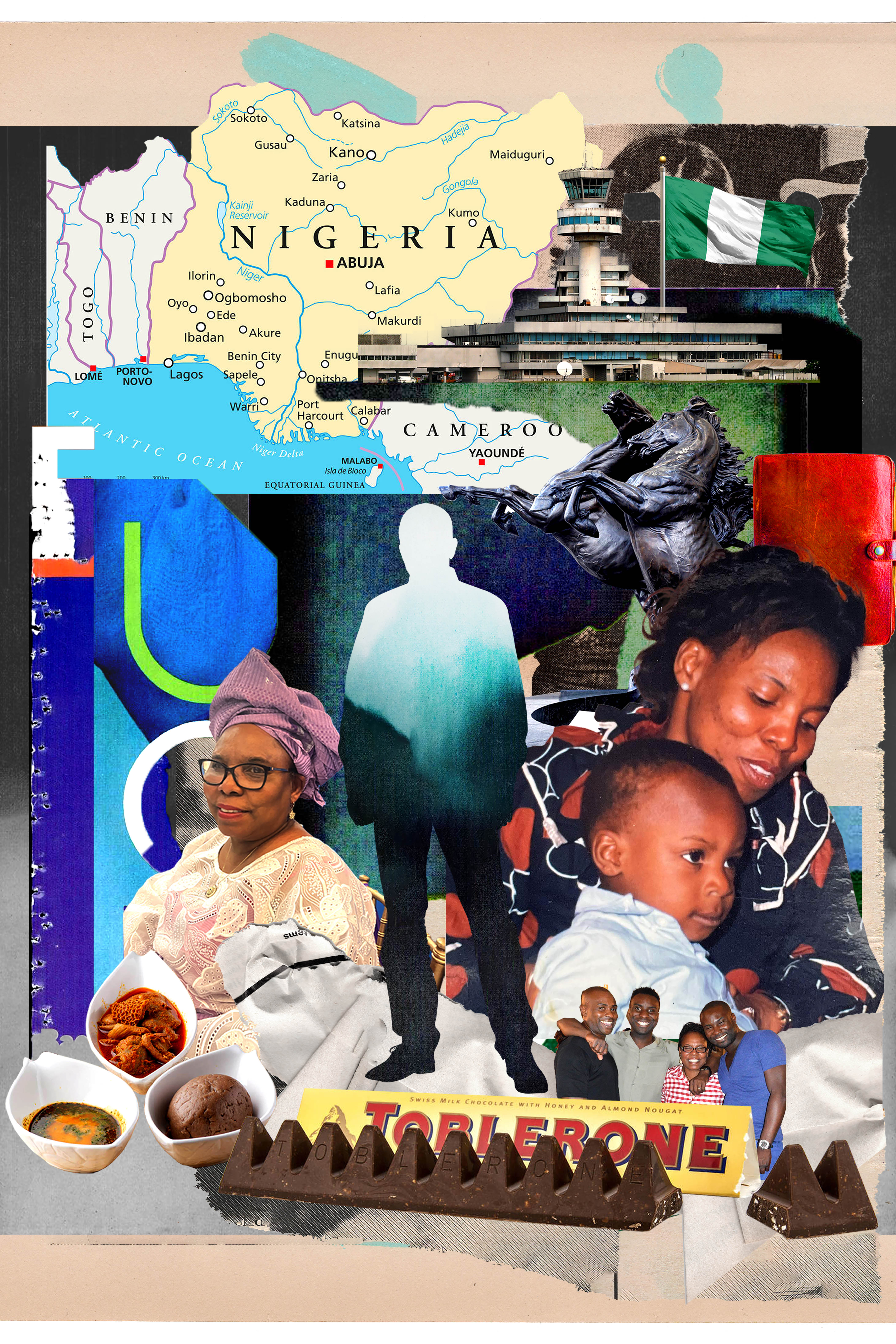

If there was Toblerone, it meant he was back. For months at a time during my childhood, my father, Olumide, would be our Yoruba Godot: a perennially discussed offscreen character whose absence shaped and defined our lives. He was the gravelled voice at the end of the phone; the person sending what money he could; the parent that I would insist, with an air of tetchy defensiveness, was not actually absent so much as tragically tethered to a Lagos-based engineering business. In the moments that he would come swaggering back into our lives, often at short notice, his trademark would be the gift of a duty-free Toblerone: that impossibly glamorous, segmental pyramid of Swiss chocolate and totem of the harried international traveller, that came in a flashing gold box and always carried the faint taste of inexpertly removed foil wrapping.

These sporadic returns would bring a familiar shift in the family energy, a realignment of demeanour and sensory environment. Dad would be sprawled on the living-room floor with his push-broom moustache and yuppy-ish Filofax. Mum would be in the kitchen, saucepan held at an angle, as she once again made one of her wayward husband’s favourite dishes: the taupe-coloured amala yam-floor swallow food that none of her children inherited a taste for. Our atomised family would stumble towards temporary nuclear status, the precise taste of which was the peace and pleasure of a part-melted hunk of nougat-flecked confectionery.

My recollections of my father are scant. From the age of around six, when my family decided to settle in the UK, his permanent residence was never the same as mine. This is a mist-shrouded period of my early life, accented here and there by his occasional returns to London in the half-decade afterwards. To concentrate hard on some of the things that I do actually remember about my father – his love of Phil Collins; an apparent carjacking in Lagos that left him with an angry wound on the heel of his foot; a photograph of him looking bemused as he emerges from the bathroom – is to open a ravaged box of stray Lego pieces. There is not much, and it is difficult to discern if any of it connects into any sort of coherent structure.

One day when I was around nine or 10 years old, I happened to be messing around with a brand-new pack of cook’s matches. I remember fiddling with the cardboard drawer of the box, and then looking on with horror as the whole thing gaped open and the entire payload of matches tumbled across the floor. Dad, who was back from Lagos, told me sharply that I needed to pick them all up. The impossible futility of the task ahead of me as well as the burning shame of having erred overwhelmed me, and my lip wobbled.

“Ah, are you crying?” he said. “Are you a baby?”

It was too much. Hot tears came as I picked up each of the fallen matches and pleaded with no one in particular, cursing my existence.

And do you know what my dad did next? As I blubbed and pleaded?

He chuckled, teasingly, and then went off to get a camera so he could memorialise my ridiculousness. To make a show of it.

Related articles:

What’s significant, I think, is that my memories of my dad are so limited that this bit of teasing has undue prominence when it comes to my sense of him. When I try to focus on the man who is the spectre at the feast of my life, when I lock in on the person whose presence I missed out on, I think of the moustachioed smile and the camera flash and my embarrassed tears.

‘My loyalty is to my mum’: journalist and food critic Jimi Famurewa reflects on his relationship with his parents, and becoming a father himself

“Oh, that was just Olumide,” said my mum, with a rueful smile, when I recalled this story years later. And that was it, as well: me and him, misaligned personalities in conflict with each other, my dad trying to counteract my catastrophising English softness with his signature Nigerian brand of tough, needling insult comedy.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

He was showing me who he was, and hoping to nudge me down that behavioural path.

What sort of man was he? Here is what I am aware of. He was born in 1947 and raised in Ilesha, a city in the Yoruba heartland of Nigeria’s south-west. He first met my mother, an upper-middle-class Lagosian princess, at university in the early 1970s. They were married in 1975; by 1976 my eldest brother, Folarin, had been born, and within seven years both Ray and I would arrive.

The early context of my parents’ relationship – my father’s sense of class inferiority, and the feeling they were somewhat mismatched in terms of temperament and culture – would set the texture of the rest of their lives and ours. The infancy of our family’s life in Lagos has a folkloric, magical hue. And I cannot help but think that there was a continuation of this magic – a kind of collective suspension of disbelief that we all continued to engage in even as we moved to London and the separateness of Dad’s existence became more obviously apparent.

That paternal void was the hole in the boat; a fact we were all jointly engaged in denying even as we baled out freezing water. Throughout this period of unpredictable contact, Dad’s presence in our lives would be marked by food as much as anything else. Not just the airport Toblerones but the trays prepared by Mum – the creamy mound of amala or pounded yam swallow; the richly carmine stew, hazardously clogged with delicate fish bones; the shallow bowl of warm water for his fingers – that were delivered to him in his upholstered throne and signalled his status as both head of the household and honoured, occasional guest.

But meals marked his absence, too. Food was everything in our family. Yet, even if I scour the deepest, cobwebbed recesses of my mind, there is not, save for that duty-free chocolate, a single memory of eating alongside him during this period. A patterned plate of softened, white-fleshed sweet potato and slurried corned-beef stew. The wonder of an egg perfectly steam-boiled in the sharply clamped folds of a Breville toastie maker. All of us gathered around the wafting fryer smell and condensation-beaded bucket of a Friday night KFC.

Meals were everything in our family. Yet there is not one memory of eating alongside my father

Meals were everything in our family. Yet there is not one memory of eating alongside my father

Dad is not in any of these formative, oft-repeated scenes, a sure sign that his active role in our lives was very much open to interpretation and a further, complicating snag in the mechanics of our relationship. To not know how we ate, to not know the shared pleasure we took from the warm heel of fresh-baked supermarket baguette devoured in the Big Sainsbury’s car park, was to not know us at all.

And yet, on and on the story went. I looked at friends and saw no parallel between our lives. Mum notes that, on hearing that my childminder’s daughter was growing up without any sort of contact with her dad, I expressed the kind of clucking, judgmental disbelief a convent Mother Superior would have been proud of. The fiction around my father’s role in our lives was that strong; a trotted-out explanatory line that I knew off by heart. Oh, my dad? Yeah, the only reason we don’t all live in the same house is that his engineering business is based in Lagos.

This was the protective fantasy and rhetoric. Never mind that, as the 1990s edged forward, landmark birthdays and achievements ticked by, milestones passed, and he wasn’t there. Never mind that, by the early 2000s, whatever financial support he was meant to be providing had evaporated to the point that Mum needed a second job. The falsehood that we were part of an unbroken, two-parent home was like a wilful lie we had been telling for so long that it no longer registered as untrue.

What’s more, there were cultural forces insulating men like my father from too much questioning or judgment. This applied in the sense of a broad societal moment – a postwar age where the expectation was that the man of the house would be an emotionally and physically distant provider, a loving tyrant who sat in the armchair with a newspaper, doled out discipline, disappeared to pubs and betting shops or out on other mysterious assignations. Free from judgment as long as he put food on the table; head of a family he was often only peripherally a part of.

But, for my dad, there was also the intensifying influence of his Yoruba heritage. Gender roles always seemed especially complex and contradictory within our culture. Though mothers, grandmothers and aunties (related or otherwise) were the visible, highly influential figureheads of our sprawled family units, it was men who were afforded deference and a kind of behavioural impunity. Relatedly, the norms of traditional village life, where it was the right of every paterfamilias to have multiple wives and many children, persisted even in modern metropolises like Lagos and London.

Then you have the fact that to live separately from your children – liberated from the more tiresome aspects of childcare in order to focus on work and making money – was a kind of memetic, self-perpetuating fashion among Nigerian men especially. We neither sought nor expected a rationalising apology for Dad’s estrangement. It was hand-waved away as an enshrined fact of culture; as unshakeable and immutable as his fondness for whipped tubers, robustly seasoned stews and the cold bitter gulp of stout. To wish him to live with us in London permanently was to wish him into being a different person.

Years later, I can look at this with some measuredness and the softening lens of cultural context. But back then, as the new millennium hit and I crossed over into young adulthood, my feelings generally formed into a low resentment, steadily simmering at the heart of my being. By the early 2000s, the fiction of Dad’s active connection to the family had been irreparably shattered. He had, as far as we knew, not actually come to London for approaching a decade, though he and my mum still spoke on the phone in an overproof-strength Yoruba that it was difficult for me to completely follow.

Those scant memories of him had begun to fade and my feelings were shifting from the specifics related to a person and more a shadowed absence; a lost or denied idea rather than a particular parental sensibility or consciousness that I was pining for. In this period, my rare conversations with him felt, in truth, like a tiresome obligation.

“Folajimi,” came the low, rumbling voice over the phone. “Do you know who this is?”

From there it would be the kind of courteous, boilerplate questions – how is school? Are you being a good boy? – that betrayed a lack of familiarity with any aspects of my life. In fact, more than that, they hinted at the arrested nature of our relationship. He had missed so much that his image of me was frozen at the point of that small child, blubbering amid a carpet of spilled matches. It was like he was peering through a telescope at the past form of a distant planet. And so he went on, trying halfheartedly to engage the little boy he had known.

Soon, this more neutral approach to what basically amounted to parental abandonment proved insufficient. My feelings were activated into something more pronounced and burning. An emotional shift that was shaped, mostly, by a deeper appreciation of the impact Dad’s absence had inevitably had on Mum’s life and circumstances; to the obvious connection between his denial of all forms of support and her palpable struggle to keep the expensive, enervating show of solely raising three children on the road.

To be clear, this was “struggle” only in the superhumanly durable sense that someone of Kofo Famurewa’s natural disposition would ever countenance it. Even at a young and especially self-obsessed age, I tended to stand back in disbelieving appreciation whenever I was reminded of Mum’s inextinguishable fire, unrivalled toughness and bottomless reservoir of generous selflessness. Her stubborn creativity and resourcefulness when it came to cooking translated to everything else.

How much could this little woman singlehandedly heap on to her shoulders without collapsing? Taking in nieces, nephews and the offspring of close friends, for prolonged, indeterminate periods? Cooking a late-night meal, propped up only by force of will and a microwaved mug of Gold Blend, despite the fact her 14-hour workday had begun with a 4am cleaning shift at a Dartford office building? Providing academic, moral and financial support to three occasionally erratic young men? Mum took all this on with the loving, determined pugnaciousness of someone who saw no alternative.

As with Dad, and his inalienable right to be an absent Yoruba patriarch, answerable to no one, this was Mum’s cultural coding. She was one of countless West African single mothers by proxy, lent indomitability by both nature and nurture. Onions, peppers and plopping cans of plum tomatoes were blitzed for stew; sweetcorn was nuked in the working microwave beneath the broken one. And, in the kitchen as in life, Mum leant into the surrounding chaos and emerged, against the odds, with something quietly extraordinary.

I recall now mum, after a last-roll-of-the-dice return to Lagos in the mid-2000s, matter-of-factly revealing to us that she’d just discovered a new, world-shaking betrayal that hinted that we were not his only dependents and that those airport Toblerones were perhaps being bought in bulk. For all Mum’s unfazed determination and sharp-tongued humour, the years of bearing so much alone inevitably left a mark. One day I found a new, hardly touched pack of cigarettes in her bag. Here was a woman who justifiably craved some relief from the pressure; here were the swan legs frantically kicking beneath my contented, happy passage through life.

It’s fair to say that when Mum called, in 2014, to tell us that Dad had died, there was no obvious shape to my feelings. Even now, the particulars of the news and how it was disseminated are hazy. I have an image of long iPhone messages from Mum and my siblings, peppered with both rote, mournful prayers and harsher, more accusatory language. There was, amid second-hand mutterings about a prolonged illness and typically Nigerian aversion to medical specificity, no clear cause of death given. The nested questions and deceptions of Dad’s time on this earth followed him into the afterlife.

His bequeathal to those that survived him was a tangled, tense communication network of semi-estranged relatives sharing information between Britain, Nigeria and America. Everyone was passing on solemn apologies and best wishes, when it wasn’t immediately clear what they were for. The regret felt formless and general. How do you go about mourning a father who you didn’t know in any meaningful way?

What I remember, in the aftermath, is the day my brothers and I went back to Mum’s for a planned conference call to discuss the particulars of the funeral. She bustled in now and again to set down food – a wibbly serving of spiced eggs, sausages split down the middle and pushed into the pan to cook quicker – variously expressing sadness at the closed chapter represented by my father’s passing and a kind of appalled wonder at the broken wickedness of his spirit.

“Ah, Olumide,” she would say, from the midst of a breathless, teeth-kissing monologue from the kitchen.

She was mournful regret and enlivening, defiant rage in conflict with each other; a twitching, kinetic mass of contradictory feelings and unsavoury revelations about Dad that she had been privy to in the past few days. And then, once we had eaten, we gathered around while one of Dad’s brothers put his case forward through the loudspeaker of a phone in the middle of Mum’s bed.

How do you go about mourning a father who you didn’t know in any meaningful way?

How do you go about mourning a father who you didn’t know in any meaningful way?

It was my Uncle Joseph – a man I had scarcely seen nor spoken to since childhood. He spoke of his deep regret and sorrow. At Dad’s absence from our lives. At the hovering toxic cloud of his other indiscretions. At the lamentable cold war that this behaviour had precipitated between the Oyeyinka and Famurewa sides of the family. Mum stood, paced, forcibly delivered some home truths; Folarin and Ray – asserting that they were no longer boys, but adults and fathers themselves – said their piece, and I did too. It felt like a moment of such uncharacteristic melodrama and confrontation that it was like it was happening to someone else.

After a few minutes of spiking tension – where it seemed increasingly obvious that my uncle was as in the dark as many of us about the particulars of his brother’s life and recent wilderness years – talk turned to the existence of an online memorial and plans for a funeral in Lagos.

“What is done is done but he was your father,” said my uncle, in a sorrowful mid-Atlantic voice. “And so I hope that you guys can head out for the burial.”

He was your father.

The more challenging and traumatic aspects of our collective experience had been given a kind of cultural cover by the idea that there was nothing unusual about my father’s behaviour; that life was complicated, marriage was hard, my dad was just another fallible Yoruba patriarch intensely committed to business interests in the country. All fair, I suppose. But, given I was in the first idealistic flush of parenthood myself, I had a building sense that to use Nigerianness as an excuse – for both parental neglect and, also, an unquestioning sense of filial loyalty – felt inadequate.

Fatherhood seemed to me something earned through consistent, active participation rather than declared via biology and cultural convention. Awaking to the challenge of it and being present anyway was the point.

And so I spoke up. I told my uncle, as respectfully as I could, that I had no desire to go to Dad’s funeral to honour the memory of someone I didn’t know.

“My loyalty is to Mum,” I said, and, resolute, I sensed what a transgressive act it seemed to deny the wishes of elders. I remember looking over at Mum, then. And though her grief still wore a scowling mask of anger, there was a faint smile on her face. A hint of something that looked like pride.

Extracted from Picky: From Fussy Child to Professional Gourmet by Jimi Famurewa, published by Hodder & Stoughton at £20

Illustration by Dakarai Akil and photograph by Lesley Lau