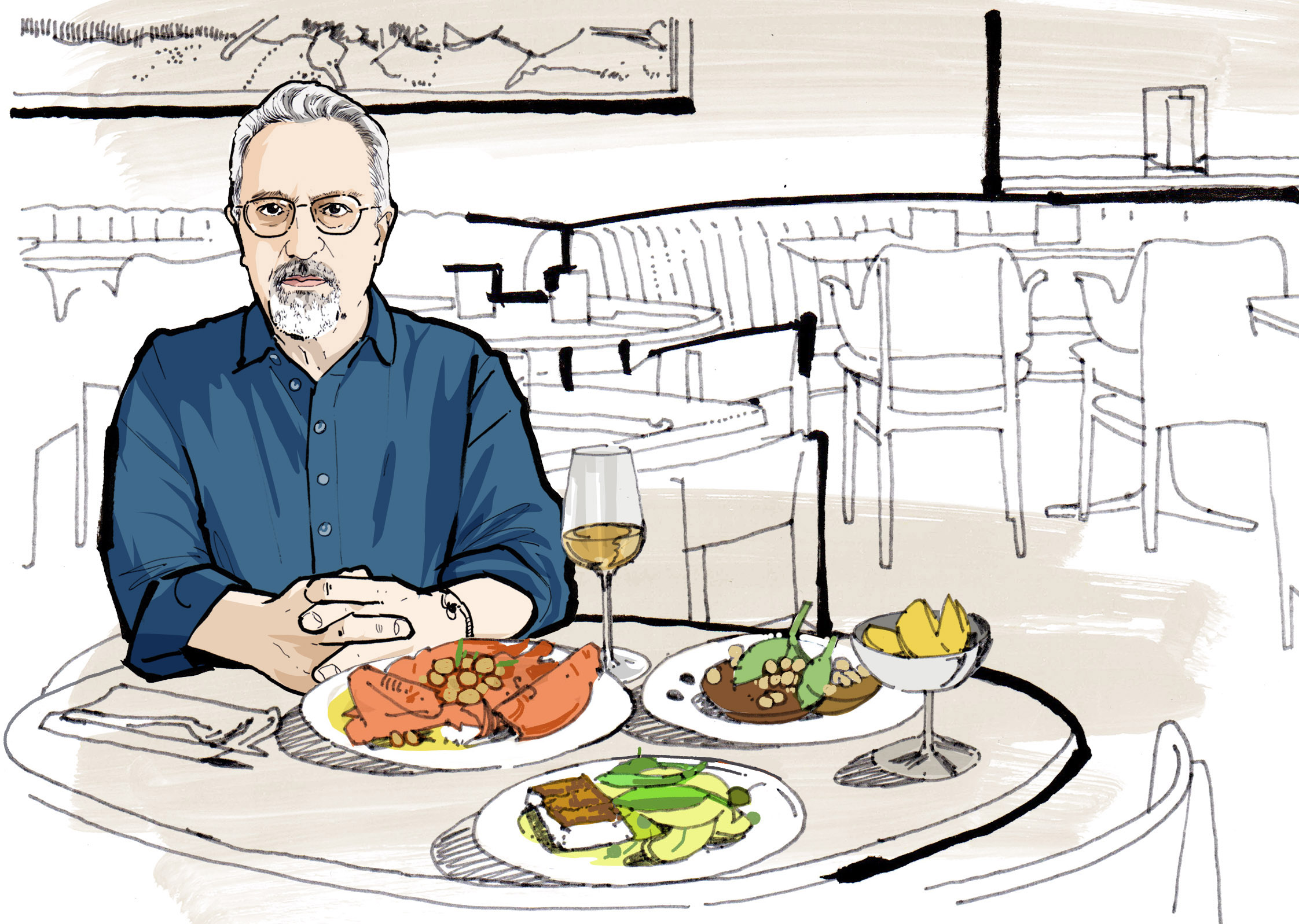

Illustration by Lyndon Hayes

Alan Hollinghurst has chosen to have lunch at Toklas, off the Strand in London. “I’ve been vegetarian for 44 years,” he says, “and I also can’t eat cheese, but they do wonderful things with vegetables here.” He orders the slow-grilled carrots, followed by the roast courgette; water not wine. “I stick to the rule that I don’t drink before six o’clock,” he says. “After that anything is possible.”

I’ve known the novelist, just a little, over many years. He always presents a lovely mix of reserve and mischief; his quite formal baritone voice, accountant’s specs and neat goatee forever at odds with a delighted half smile and side-eye twinkle. His writing – I’d make the argument that Hollinghurst is the peerless prose stylist of his generation – has the same qualities: the fastidious syntax of unspooling sentences in tension with masterly layers of quiet irony and wicked observation. The priapic excesses of his debut, The Swimming-Pool Library, a book that among other things heralded a liberated new frankness in the description of gay sex in the English novel, has evolved into a body of work alive to all registers of class and manners and subtly shifting emotion, exemplified in his Booker-winning The Line of Beauty (about to be a play).

Hollinghurst’s latest book, Our Evenings, now out in paperback, is something of a climax of those interests. The book charts, in the author’s easeful way, an intimate history of gay love and race relations from the promise of the 1960s to the tragically hardening realities of the present day.

Hollinghurst once told me that, partly by necessity, he had lived the first half of his adult life almost in reverse – buttoned-up restraint in his 20s, giving way to more abandoned licence in his 30s and 40s. Now 70, he has long lived in the same flat on the edge of Hampstead Heath, and though he says he has come close to committed cohabitation once or twice – “and I don’t think I’m hard to live with” – his vocation, he suggests, has always exerted more powerful demands. “There are times when I just have to protect being at my writing desk,” he says.

Hollinghurst is enjoying a long hiatus between books, half-relieved to imagine he might not write another, knowing full well that he will

Hollinghurst is enjoying a long hiatus between books, half-relieved to imagine he might not write another, knowing full well that he will

As our starters arrive – my tomato dish bringing all the intensity of their advertised origin in the volcanic soil around Mount Vesuvius, the sweetness of his carrot dish sharpened by pistachio and sumac – he explains how he is enjoying a long hiatus between books, half-relieved to imagine he might not write another, knowing full well that he will. “My wonderful publisher, Mary Mount, has just trustingly contracted a new novel,” he says. “My cycle now seems to be about six years [for each book], so I think she’s not expecting anything just yet …”

At what point in this cycle does he sense a new novel stirring?

“Generally, I have to say, I have ideas a bit sooner than this,” he says. “Henry James had a good thing about the germ of a book, he said it was like ‘planting out the seedlings in the sunny south window’ and waiting to see what happens.”

Our Evenings is the story of Dave Win, a child of the war – his father a Burmese civil servant who he has never met, his mother a seconded English secretary. It germinated, Hollinghurst recalls, out of a few elements. “My mother died in 2016,” he says, “just when I was finishing my previous novel.” Betty Hollinghurst was 97, and her son, an only child, had long been, at a distance, her consistent carer. “So some things formed around that.”

The house clearing in Gloucestershire involved going through “huge, tatty, manilla envelopes, hundreds of unsorted photographs”, which gave a sense not only of the mysteries of his parents’ lives – his father had been stationed in the Bahamas during the war and came back from Nassau to be a deputy bank manager in the rationed home counties; the pair met when he stayed at a hotel in Stroud, where Elizabeth worked on reception – but also of the shadows of lives in his school photographs. He was reminded of a friend from that time, half-Burmese, unique for his parentage at Hollinghurst’s prep school. “I’d had on my mind for a long time to try to write about times I’ve lived through from a different racial perspective,” he says, “trying to find a way that will be interesting and sort of tactful to do it.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

As a novelist he has long been drawn to outsiders’ eyes – “there is probably some deeply embedded thing about being gay in that”, he says, “but also it’s a useful perspective for being intrigued about everything” – and he finds that voice, at one remove, for Dave.

He is pitch perfect at reinhabiting schoolboy society in his book, mapping Dave’s interior life as he finds ways to fit in. “I remember that thing myself,” he says. “Like Dave, I suddenly found I was quite a good mimic, and that gave you some cachet. And also that I was quite good at reading aloud – I did actually do that thing of reading PG Wodehouse stories to class after prep – and doing all the voices.”

Alan ate grilled carrots with labneh, pistachio and sumac, £15; roast courgette with coco beans, tomato, and olives, £22; alphonso mango with chocolate sorbet, £8. Tim ate Cuore del Vesuvio tomatoes, £16; hake with courgette, potato and basil, £28; alphonso mango with chocolate sorbet, £8. Alan drank a bottle of still water, £4, and Tim drank a glass of Toklas white wine, £12

Dave’s frank enjoyment of his homosexuality, as he ages, is in contrast to the closeted relationship written for Dave’s mother with the female “companion” she moves in with. The attitudes if not the facts were borrowed from his own mother, he suggests.

What did Betty make of his books over the years?

“She sort of read [The Swimming-Pool Library],” he says, with a giggle. “And decided they probably weren’t her sort of thing. I didn’t really allow myself to think about the embarrassing side of it.”

He never really came out to his parents, he says. “It was this English thing of never talking about it. That silence was one thing I was trying to recreate in the book. My father was certainly unsurprised; my mother … I think she didn’t want it to be the case, so she didn’t allow herself to imagine it,” he half-smiles. “She probably had problems when she was accosted by her friends in Waitrose who asked, ‘What was this about Alan’s book?’ I have no idea what she said. After the first one, she would ask, ‘Would I like this one?’ And I would say, probably not.”

We’re on to mango sorbets by now, a welcome iciness on one of the hottest days of the year. The restaurant’s sliding doors are open and the tables out in the sun are spotlit by a fierce sun. In our vaguely air-conditioned corner Hollinghurst is detailing both his abiding passion for music – his spare bedroom full of LPs has given way to an obsession with the Idagio app, that allows him to compare, say, a dozen interpretations of a single Beethoven sonata while doing the ironing – and his newer love affair with auction sites.

“The older I get, I find art – painting in particular – more and more involving,” he says. “Unfortunately, at exactly the moment auction houses started putting their catalogues online, I found myself with a bit of extra cash. I wouldn’t be able to calculate the number of hours I spend scrolling. I have lately been looking for an Edwardian painter called Paul Maitland, who really only painted gardens in Chelsea and Battersea, sometimes tiny ones, but they are absolutely magic to me.”

Despite these solitary impulses, Hollinghurst loves a party. He has, among other things, been able to move among social gatherings in his books in a manner to rival Henry James or Scott Fitzgerald. You sense him in the restaurant catching little inflections of conversation on other tables. He doesn’t cook – “do people still give dinner parties?” – but he enjoys a big night out. “I had a wonderful party for my book at the Coronet Theatre in Notting Hill,” he says. “The launch was in the bar, which used to be the stalls. It has this alarmingly sloping floor which was rather wonderful. And then speeches under the great dome of the theatre. I got a wonderful young pianist to play a little bit of Janáček’s Our Evenings, from which the book takes its title.”

Does that memory make him look forward to the next one – is he still, seven novels and counting, as excited about writing as ever? “I have to say, when I have finished each of my last three books, I have thought: I must never put myself through that again,” he says. “I would love to be able to write a short book. A novella. But no, of course, when I am properly in a scene, I just adore that – seeing it all and making it happen."

Toklas, 1 Surrey Street, Temple, London WC2

Our Evening by Alan Hollinghurst (Pan Macmillan, £9.99) is out now in paperback. Order a copy for £8.99 at observershop.co.uk