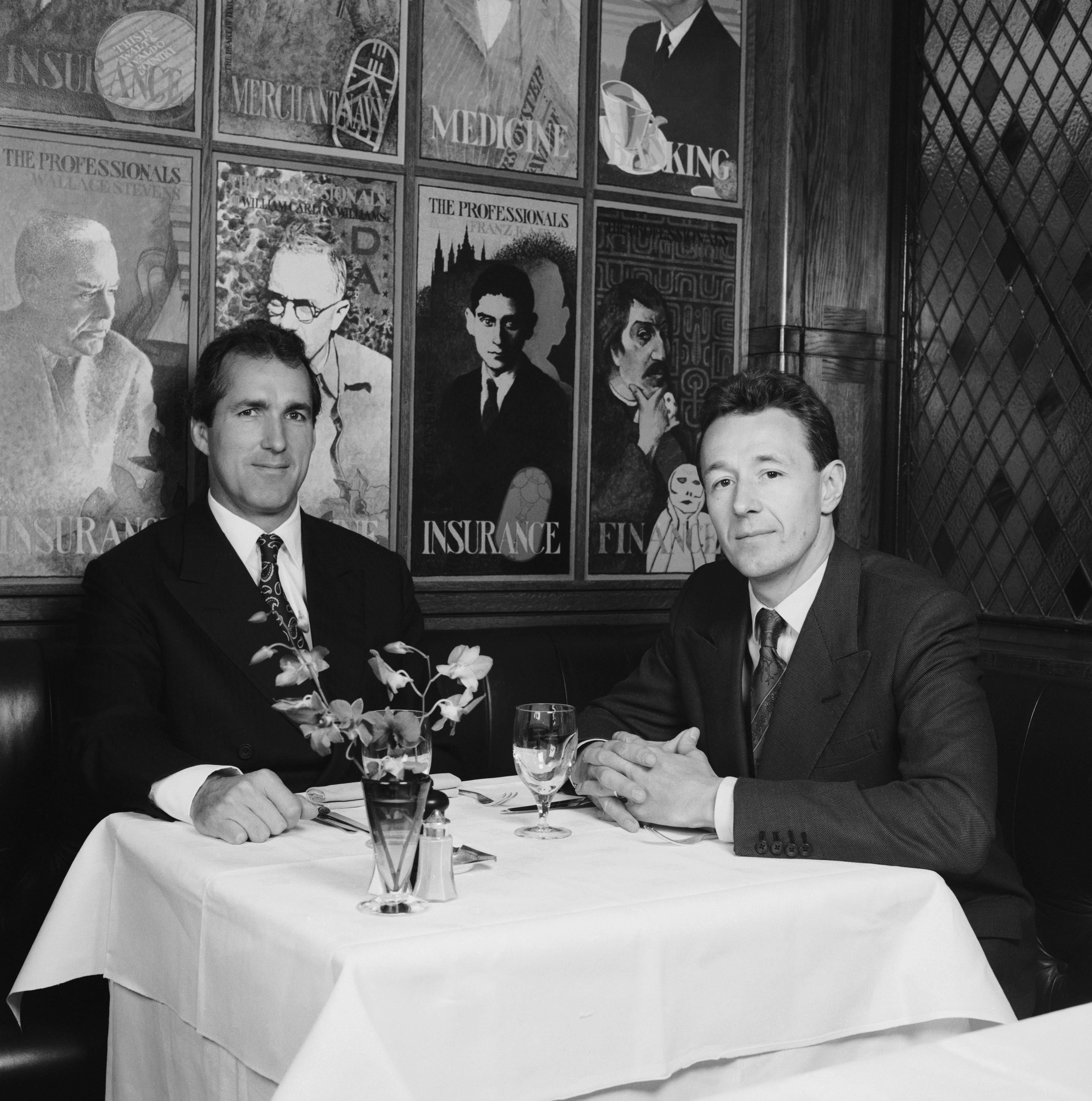

Photograph Suki Dhanda

At the tail end of the 1990s I was working for a successful men’s style magazine. It was a golden age, in the sense that we were not haemorrhaging readers (yet) and still had money to have parties and take taxis and other things we understood to be a journalist’s birthright. To celebrate, our boss announced he would take everyone on staff out to lunch individually. We just had to tell his PA which restaurant we wanted to go to. One (an ornery sub-editor) opted for the Guinea Grill, a meat-forward Mayfair pub. Everyone else – all 22 of us! – chose the same place: the Ivy in London’s West End.

Looking back, it seems impossible how dominant the Ivy was then in London’s food scene: everyone wanted to eat there. Guy and Madonna, Brad and Gwyneth, and Richard and Judy were all regulars. Hollywood royalty (Jack Nicholson, Angelina Jolie) competed with genuine royalty for the best tables, or with Tom Stoppard or David Beckham or Kate Moss. Jennifer Lopez was, according to legend, allegedly barred for changing her reservation too often. Before social media, the Ivy was Instagram: the place you went to find out what famous people were up to, and with whom.

The pull of the Ivy was not a chef. No one knew, or much cared, who cooked its solid, comforting staples. The lure instead was that the restaurant was run by Chris Corbin and, most conspicuously, Jeremy King. Creating a hit restaurant is supposed to be like alchemy, but Corbin and King have done it again and again: first with Le Caprice in the 1980s, where Princess Diana was a regular, then the Ivy, then J Sheekey and, from 2003, the Wolseley. The pair are, no question, Britain’s most influential restaurateurs of the last 50 years.

Sitting down for breakfast with King, 71, at one of his new establishments, the Park in Bayswater, I tell him about my one brush with the Ivy. He smiles. “I don’t think London will ever see quite the same concentration of celebrity in a restaurant again. It just hit the moment. Not from the beginning, though… I remember when we opened on Saturday lunch doing a zero.”

King means that literally no one came in: a nightmare for any restaurant owner. “It was chilling,” he goes on. “It was the same in the beginning of Le Caprice. We were, of course, helped immensely by the Princess of Wales’s endorsement, but we had some really difficult times earlier on.”

What turned it around? King thinks for a moment on how to encapsulate the wisdom of a lifetime in restaurants. “It was the mix,” he decides. “It was the blend.”

It’s strange speaking like this with King. He has always been a visible figure in his restaurants, stopping by tables for a quick gossip, and at 6ft 5in he’s hard to miss. But he has largely sidestepped sit-down interviews. He did one when Le Caprice opened in the early 1980s and then remained gnomically silent until 2012, when Brasserie Zédel launched in Piccadilly Circus. He still doesn’t have a Wikipedia page (which sends me down a rabbit hole researching famous people in public-facing fields without an entry. Answer: it’s very rare).

King’s reason for avoiding interviews is typical of a man who has made a career from diplomacy and impeccable manners. “We had a lovely relationship with the press,” he explains, “but if I said, ‘OK, I’ll do an interview for you,’ somebody else would say, ‘Why wouldn’t you do it for me?’” King also believes that restaurants are most exciting when they have a frisson of mystery. “I had to ask Andy Warhol not to take photographs in Le Caprice.”

King is breaking his silence now because he has a (charming, insightful) book to promote, Without Reservation: Lessons from a Life in Restaurants. He has been pestered for decades to write a memoir by the legion of literary agents who frequent his establishments. But the time never felt right. “Circumspection” is a big quality for King. He didn’t want it to look as if he was cashing in or piggy-backing on the notoriety of his famous clientele.

“We should never profit from either the misfortune of others or the cost of somebody’s demise,” he says. “This book would have been absolutely impossible 20 years ago, even 15.”

Jeremy King and and fellow London restaurateur Chris Corbin, circa 1995

But during Covid, King found himself with time on his hands. There was a surge in 80s and 90s nostalgia, a wave ridden by memoirs from New York restaurateur Keith McNally and magazine editor Graydon Carter. King also had a realisation: while the restaurants he and Corbin created are ephemeral, a book might allow those spots – time capsules of a past age – to live on. Plus, lots of the lead characters are no longer around, which simplifies matters. King sighs: “Most of the people I’ve talked about in any detail are dead.”

Nevertheless, King retains some reticence about stepping into the spotlight. He sips his coffee. “When somebody pointedly looks at me, I’m more likely to look over my shoulder to see who they’re looking at. It’s just my nature.”

King grew up, mostly uneventfully, in Burnham-on-Sea, Somerset. Aged nine, he won a scholarship to a Sussex boarding school and disappeared there for a decade. A smart child, the family joke was that he would become prime minister. But after school, he became obsessed for a few years with Luke Rhinehart’s novel, The Dice Man, about a bored psychiatrist who throws a die to make day-to-day decisions. King earned a place at Cambridge University, but the roll of the die decreed he turn it down – a decision he regrets to this day.

“There has to be danger,” he says now. “With the Dice Man throws, there always had to be the potential for a bad outcome. But not catastrophic. Maybe it emancipated me from my inhibitions and, as time went on, I’ve become more confident. But I still like a bit of risk.”

King was also a skilled gambler. He made quite a bit of money in his 20s, especially on horse racing, but these days he doesn’t like how a flutter makes him feel. Not so long ago, he found himself in Las Vegas, meeting someone who wanted to bring King’s restaurants to America. About to hit the blackjack tables, he stopped. “I thought, ‘I don’t want to do this,’” he recalls. “I remember the word I said to myself, ‘It feels masturbatory.’”

I don’t think London will see quite the same concentration of celebrity in a restaurant again

I don’t think London will see quite the same concentration of celebrity in a restaurant again

It’s not immediately easy to square this image of the card-counting shark with the elegant man in front of me in a Timothy Everest suit and white pocket square. King doesn’t always dress in tailoring, but people who’ve known him for years have never seen him wear anything else. “A year into the Wolseley, I had to go in on a Saturday morning, unexpectedly,” he says. “I was just wearing slacks and a sweater, and this waiter came out with a big stack of plates from the bar that she’d just cleared and looked at me and dropped the whole lot.”

In other ways, his interest in risk makes sense, having picked such a precarious profession. There have been downs as well as ups, notably in 2022, when he lost his restaurants after falling out with a key investor, a Bangkok-based hospitality mogul called Minor International. In 2017, the company bought a 74% stake in Corbin & King – including the Wolseley, the Delaunay and Brasserie Zédel – for £58m, but clashed over whether to expand into the Middle East and Asia (Minor claimed King blocked the move).

It quickly became ugly. Minor forced Corbin & King into bankruptcy and their nine restaurants were put up for auction. King secured new American backers, but they lost the pissing contest and Minor paid £67m for the remainder of the company’s equity, plus debts.

King calls that period, a scarring one, his “premature retirement”. He licked his wounds at home with his second wife, an interior designer (he has three grown-up children from his first marriage, including Jonah Hauer-King, who is doing well as an actor), and worked on the book. But he bounced back, this time without Chris Corbin.

“Friends have said, ‘You were so brave to go back in,’” says King. “And I said, ‘Actually, no.’ I wasn’t financially in a position to retire and I wasn’t mentally in a position to. I felt I had no option.”

Much has changed in his industry. Chefs tend to dominate the scene, not restaurateurs. Margins are tighter than ever. There are no longer editors with expense accounts to treat 22 members of staff to lunch. King says he will never pick a favourite of his restaurants, but I ask for his most cherished era. “I think the heyday of modern society is probably the 1980s and 90s,” he says. “It was a lot of fun, but it also felt more real.”

In 2024, King opened the Park, where our breakfast is now wrapping up, and also Arlington, on the site of Le Caprice. Later this autumn, he is back with his largest restaurant to date, Simpson’s in the Strand. A vast space next door to the Savoy, it first opened in 1828 and was formerly frequented by those influencers of olden times, Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle. It has been closed since 2020,

“The climate for restaurants is terrible for everybody, one way or another,” says King. Then he grins, perhaps that gambler’s instinct. “But I think if we’re good enough, we transcend it – that’s part of the pleasure for me.”

Jeremy King is the author of Without Reservation: Lessons from a Life in Restaurants, published by Fourth Estate at £25. Order a copy for £22.50 from observershop.co.uk

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy