On a wet evening in January, I found myself in a narrow, amber-lit London bar called Ellie’s, where men who had spent a great deal of money to dress like midcentury Breton fishermen were pressed close to women in lovely dresses, their glasses of riesling misting in the conversational air. The crowd had turned out for a book reading, part of the Soho Reading Series, a roaming literary night at which novelists, essayists and poets read aloud to an audience that is encouraged to drink and flirt and stay out late.

Founded in 2023 by a 32-year-old academic named Tom Willis, at least one event is held each week. Willis often opens evenings by inviting the audience to find, kiss, and take home someone they like the look of, not so much reinventing the book reading as reawakening it with the energy of a Vanity Fair party circa 1995, a time when Condé Nast editors had personal drivers, when writers could become household half-names – Kerouac, Salman, Sontag – without first having built a career on television, and when literary careers were often launched in parallel to affairs.

Last year, a YouGov report found that 40% of Britons had not read or listened to a single book in the past year, a fact contrary to Willis’s success: in the three years since launching his events, he has sold some 6,000 tickets, mostly to people in their late 20s, the age group whose engagement with reading is reportedly the lowest. The nights have attracted optimistic write-ups in glossies like Vogue. And while the numbers won’t propel an unknown novel up the bestseller list, the noise around Willis’s events has been loud enough to draw the famished gaze of publishers, members’ clubs and fashion brands, all keen to be associated with whatever this might be – or might become.

Novelists, essayists and poets read aloud to an audience that is encouraged to drink and flirt and stay out late

Novelists, essayists and poets read aloud to an audience that is encouraged to drink and flirt and stay out late

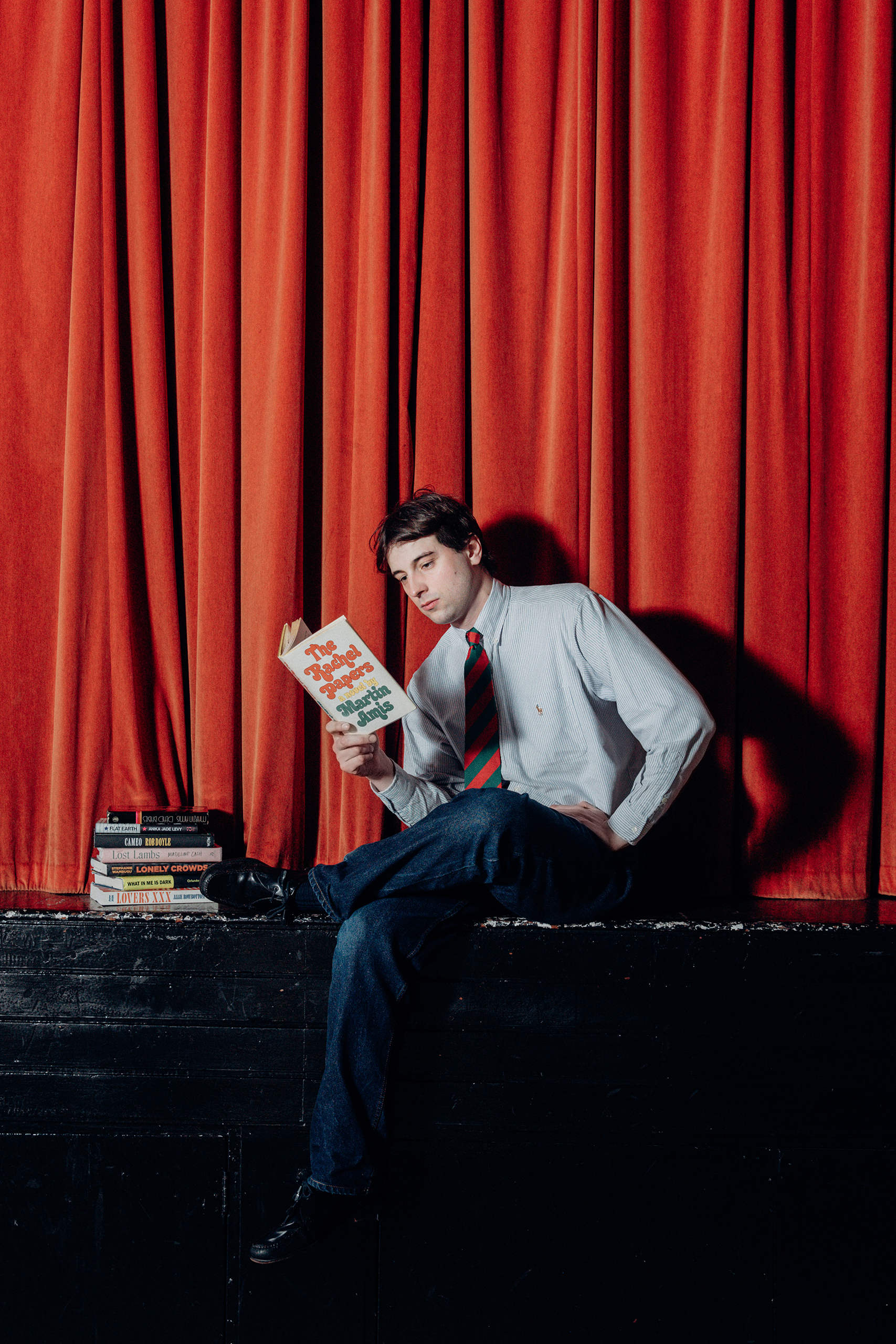

Willis arrived at Ellie’s a little late, apologetic yet buoyant. He is tall and slightly foppish, with a Disney prince flick of a fringe and the accessible appeal of a Richard Curtis lead. He had a severe cold, and immediately ordered a lager to fizz the edge off it. The room was already thick with writers – aspiring, established, some no doubt flailing – alongside a drifting cadre of Oxbridge arts graduates born a decade or so too late to secure the job-for-life at the BBC or Random House that their predecessors once assumed was their birthright.

At eight o’clock, Willis took a mic, promising the crowd he’d keep introductions short. Behind him sat the Irish author Rob Doyle, there to promote his bracing new novel, Cameo. After pointing out that the evening’s chair, the writer Andy West, was wearing a vintage Armani blazer – “Look at it!” Willis said – he apologised for his own outfit, which he thought shoddy in comparison. Fashion was a preoccupation of the evening, as was the state of the book industry. West cited a statistic lifted from the Times Literary Supplement: only 5% of published authors make it to a fourth book, which made Doyle, already on book five, one of the lucky/talented few. The implication hung in the air. And yet: here we all were.

On paper, the Soho Reading Series is a classic publicist’s event: an author reads aloud to promote their latest book, a concept as old as publishing itself. The often-heard criticism of these kinds of newly fashionable literary events is that the author and their book are incidental. People come to be seen; to drink; to skip the dating apps and touch the source; to, if the night goes a certain way, experience an inciting incident.

Still, the literary events of the 1980s and 1990s were hardly sober affairs, either. Both the novelist Martin Amis and the former New Yorker editor Tina Brown recounted their first meeting at one such literary party, a coup de foudre that, as Brown wrote, “became a longer evening than I expected”. That didn’t seem the way of things at Ellie’s; the audience was respectfully attuned to Doyle’s readings, though I found this to be understandable: each one contained an unignorably vivid description of sex.

Book club culture: Martin Amis and the former New Yorker editor Tina Brown at literary party for his book The Information in 1995

As soon as Doyle finished, Willis moved through the crowd like a practised host, pulling people into his orbit. At my stool he gave me an enveloping hug and immediately apologised for infecting me with his cold. When his girlfriend arrived moments later, so pretty I almost lost my footing, they kissed, fully and unselfconsciously, inches from my face.

I wondered then: is everyone here about to…? Or maybe, with the car and the kids and the three-Kindle-pages-before-I-pass-out nightly routine, I had simply forgotten how these rooms typically work. That, after all, is the promise of the Soho Reading Series: something Jane Austen-esque in spirit. Not escapism, exactly, but the suggestion that stories might still rearrange the social order, and that something delicious and unplanned might follow.

Sometime later, Willis prised apart from his girlfriend. “Sorry,” he said, with a crooked smile. “I better give out some books.”

A few days later, I am sitting at a corner table in the pub Willis suggested we meet, near his east London home. He is late. “Sorry,” he texts. “I went to the wrong pub.” Ten minutes later he arrives and greets me like a beloved schoolfriend, making it immediately clear how he persuades high-class writers to endorse his events. Still, relatively little is known about him. Based on his well-to-do accent and the Tatler-adjacent demographic of his events, people assume some sort of hereditary pedigree, and he does not rush to correct them unless asked directly. I ask directly. “Look,” he says, “I’m not a frigging duke.”

Willis did, however, grow up on an estate near Montgomery, in mid-Wales, where the garden was measured in acres, not metres. As a child he rode horses while wearing an Alexander the Great costume his mother had made for him, then rowed across the family lake. It was, he says, “like something out of a cartoon”.

When he was 13, however, his parents divorced. His father, an investor in film and property, left and, Willis claims, took what remained of the money after the ruinously expensive proceedings. Willis and his brother moved into a modest house with their mother, who eventually became a cleaner, earning £10 an hour to cover the bills. Willis became a “screw-you teenager”, expelled from school, turning to drugs to numb the shock of his abruptly altered life. He stopped reading – until then his favourite pastime – and failed his A-levels three times. “I became a fail-son,” he says. “I took no pleasure in the world.”

Eventually, he knuckled down enough to secure a place at Cardiff University, where a tutor, spotting something salvageable, encouraged Willis to spend a year in Athens with the British School of Archaeology. There, surrounded by students who made no effort to hide their intelligence, Willis began reading again and, slowly, he began to like himself, too. When he returned to London, he enrolled in a master’s programme at University College London. A doctorate in English Literature and Classics followed. “Penance”, he says, for his wasted teenage years.

'I feel so much more inspired when I read a little… I wanted to be around people who felt the same way': Tom Willis

While drafting a thesis on WH Auden and antiquity, Willis fell into a love triangle with a woman who, having just moved to New York with her boyfriend, declared her impossible love for him. Scrabbling for a way to reciprocate, Willis found an exchange programme at Yale, which offered proximity to the girl and an Ivy League affiliation to exorcise the lingering shame Willis now felt about not having attended Oxford.

Once in New York, Willis slipped into the downtown arts scene and every weekend he attended a different literary party. Until then, his experience of book events had been limited to polite readings at Foyles. In New York, the format felt reborn. “People were smoking, reading bits of plays in abandoned brownstones,” he says. “Famous writers were there. Everyone was young and dressed up. They cared about partying and literature.”

Willis became friends with the New York-based literary critic Christian Lorentzen, a contributor to Harper’s and the London Review of Books. Lorentzen places the rise of the events Willis encountered within a post-pandemic loosening of literary infrastructure. In New York, there has long been a culture of readings that take place outside bookstores and formal publicity circuits, he told me recently, but since Covid that tendency has accelerated. Younger writers, raised “on the internet rather than on what are now called legacy magazines such as the New Yorker or the Paris Review,” realised they could simply do it themselves. The result has been a swell of magazines, readings and parties operating beyond traditional institutional channels, a shift that, Lorentzen suggests, reflects the fact “there’s an upswell of good writing happening outside the usual channels. If there wasn’t, none of this would exist.”

Willis is ‘reawakening the reading event with the energy of a Vanity Fair party circa 1995’: editor Graydon Carter with author Fran Lebowitz at one such party in New York.

For Willis, the weekly literary party became a form of mind, body and soul pilgrimage. “I feel so much more inspired when I read a little,” he says. “You have these sentences in your head, then you step outside, awake to the thrum of life. I wanted to be around people who felt the same way.” When his year in New York ended, he returned to London, determined to recreate the nights he’d loved in the US. The woman he’d followed to America had since broken up with him; perhaps, he thought, if he could build a similar book scene in London, she might emigrate, too. (She did not.)

Here, privilege played a vital role. Willis’s father had just bought Blacks, the private members’ club founded in 1764, opposite the Groucho Club on Dean Street, and he agreed to let his son host a trial event. Fifty people turned up to that first night, including several figures Willis describes as “micro-celebrities” from the New York literary scene.

One of those in the audience was Olive Parker, a creative director in her late 20s, who had recently returned from a stint living in New York. She came across the event at Blacks via Instagram. “Weird place,” she recalled recently. “But everyone was interesting in different ways.” There were six readings that night. “Some people did non-fiction, some poetry, others autofiction. Some of it was very serious; some of it very funny.”

From the outset, Willis was unapologetic about what he was trying to build. “I came back with this very American enthusiasm,” he says. “I was pretty shameless. I told people: this is a scene. This is cool. You are cool.” Parker recognised the ambition immediately. “He did an amazing job of bringing together the things that were fun about New York, which London kind of lacked,” she told me. “Community, for one. There weren’t many places you’d go where your friends would definitely be there, or where you’d make new ones. He managed to create that spirit.”

After the first few events at Blacks, Willis began booking venues elsewhere in the city. People attended, then returned with friends. And as the reputation of the event built in stature, so did the names on the bill.

‘I was pretty shameless. I told people: this is a scene. This is cool. YOU are cool’

‘I was pretty shameless. I told people: this is a scene. This is cool. YOU are cool’

When Geoff Dyer, one of the few genuine grandees of English letters, first met Willis, he was at a vulnerable moment, ego-wise. He had recently been touring Homework, his memoir of growing up, and the experience had left him dispirited. “It included a couple of quite frankly dismal old-school events in bookstores,” Dyer told me recently. “Everything felt a bit worn out and half-hearted – and very badly attended.” Willis told Dyer that he ran reading events that reliably attracted hundreds of people, and Dyer signed up. Then he learned that the venue Willis had booked for his event was in Walthamstow. “That,” Dyer told me, “was a bridge too far.”

Dyer cancelled. Willis regrouped, soon returning with a more extravagant proposal: a Geoff Dyer gala evening. “It really was a lot of people,” Dyer told me. “A properly riotous atmosphere.” (The gala was held at the Mandrake Hotel, technically Bloomsbury, but Soho-bordering.) “There was nothing dismal about it at all.”

Dyer, as the headliner, was last to step up to the microphone. “I’ve done enough readings to know that, while your ego’s pleased to go last, quite often what that means is that by the time you reach the stage everyone’s had enough,” he said. “But in this case they’d all stuck around.” Dyer harbours no illusions about the crowd’s motivations. “A lot of them were there to drink and party,” he said. “But a light dusting of literature on a good night out sounds great to me? And they can’t stay at the party forever. When they get home, maybe they end up reading a book by an old duffer like me.”

Not everyone is convinced by the series’ reputation as a matchmaking engine. Parker thinks the dating aspect is oversold. “I wish that was more the vibe,” she says. “But every time I go it’s just a bunch of guys looking at the girls, not really talking to them.” At Ellie’s, an attendee described the crowd as “The most beautiful women you’ve ever seen – and 20 of the weirdest men.”

For Lorentzen, the recurring question of whether people attend the new literary events for the books or the party is beside the point. “I don’t really think that debate is very interesting,” he says. If people only wanted to socialise, “there are plenty of places to do that any night of the week.” A reading, by definition, involves listening. Scenes, he adds, are not measured against some idealised historical salon, but are “put together by whoever is around, who’s active, who’s writing” – a contingent mix that shifts over time. “If they didn’t care about writing at all, they wouldn’t be there.”

The write stuff: the crowd at one of the Soho Reading Sessions (this one part of Lost, an artist-led club night).

Not every author is able to read their work aloud to a crowd. In fact, Willis has only come across a few that really can, and the variability in quality of performance has, at times, resulted in poor reviews. On Reddit, one user described the evening she attended, in 2025, as “slightly mortifying”, complaining that “terrible, muddy prose was being elevated into a spectacle for dishonest reasons – mostly so rich young people could get together and play-act as literati”. The event, she added, was for “social climbers and waifish young women looking for artistic-yet-still-wealthy boyfriends.” (Austen’s ghost: take note).

Of the criticism, Willis says, “People love shitting on things,” but then he claims to welcome it: bad publicity, he notes, has a way of lodging in the mind. More substantively, other observers have pointed out that both the audiences and the authors at Soho Reading Series events tend to skew white and middle-class. Willis doesn’t dispute the fact, though he resists the idea that it is either unique in the industry or easily remedied. “I do try to balance it out, to be representative,” he says. “I don’t kneecap myself with language, but I recognise I have a responsibility.” The social coding of the events is, in this sense, less an anomaly than a reflection of the wider literary culture in which they sit, one shaped by class, education, and access.

For all this, Willis’s events are becoming more frequent; sometimes there are as many as two a week. Willis, who now works in PR for universities, does not yet take any money from the project. But commercial interest is growing. The Groucho Club, a storied haunt of writers and artists in its heyday, offered to host several Soho Reading Series events, presumably hoping to entice the next generation of members. Drake’s, the elegant, influential menswear brand, sponsored the Geoff Dyer gala, and dressed the author for the evening. “I’m used to getting free books,” Dyer told me. “But the idea of getting a suit – that was really good.” A few days after the gala, Dyer was booked to appear at the Cheltenham Literary Festival. He was tempted to ask for more clothing, he told me. “But that might have been pushing it.”

Willis is currently selective about which collaborations he accepts. “I don’t really like those readings where Prada’s sponsoring,” he says. “That’s goofy as hell.” He pauses. “I mean, I would do it. For enough money, sure.” He is also clear the project has a shelf life. “I don’t want to be, like, 38 and still doing this,” he says. “I don’t want to be the oldest person in the room. But it’s given me opportunities. I’ve got a tiny profile in the world of literature. Maybe it’ll help me sell my novel.”

‘If they didn’t care about writing at all, they wouldn’t be there’

‘If they didn’t care about writing at all, they wouldn’t be there’

The modesty of the ambition is telling. The names involved in nights like these are not billboard famous, but these days which writers’ names are? Today, Sally Rooney sits alone at the summit of household literary renown. Besides, Dyer believes the most interesting fiction-writing is happening on the margins of the publishing industry. In Lorentzen’s view, Willis has “pretty good taste”, though he acknowledges that assembling a line-up is always “a hit-or-miss kind of craft”. What he values most is Willis’s willingness to give writers time. For most working writers, recognition arrives slowly, if at all, and often feels anaemic when set against the scale and velocity of the present moment. We live amid rolling catastrophe, political theatre, algorithmic exhaustion; our days are mediated through screens calibrated for maximum stimulation. Against this backdrop, literary success has never felt more marginal.

Yet that may be precisely why events like the Soho Reading Series have re-emerged, a counter-rhythm to the digital world: bodies in a room, voices haphazardly amplified, attention briefly undivided. In an age when so much cultural participation is flattened into the treacherous metrics of likes and follows there is something radical about gathering for an activity that cannot be optimised. If you don’t like one reading you can’t just skip to the next. Here the book is not a content unit but a pretext: a reason to assemble, argue, feel like a living body in the world.

None of this was accidental. Willis’s insight was not that people needed more books, but that people who love books needed a better reason to gather in the same room. After all the glinting coverage, as the diary fills and the trickle of offers swells to a stream, Willis doesn’t know how long the momentum can be sustained. But what he returns to most often is not the possibility of landing a book deal, but the hope of doing well enough to let his mother retire.

“People are so rude to cleaners,” he says. “They feel like they can treat her however they want.” Whenever that happens, she has told him, she focuses not on what they’re saying, but on her son being mentioned on the cover of Vogue. Because of reading.

More information at @sohoreadingseries

Tom Willis portrait: Jonathan Daniel Pryce. Archive images: Dafydd Jones; Getty

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy