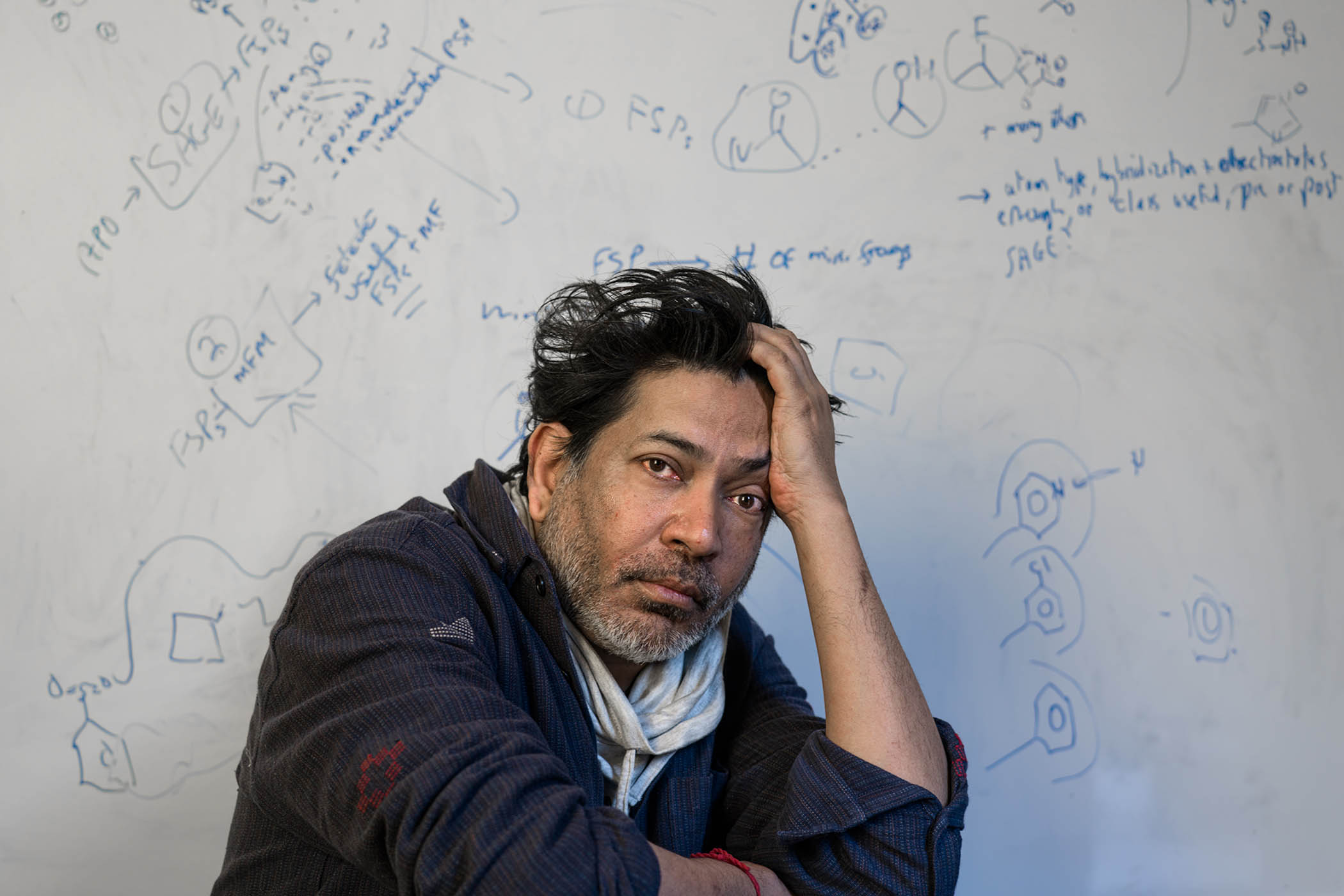

Portrait by Maria Spann

The first thing I do when Siddhartha Mukherjee logs on to our call is thank him for helping me quit smoking. When I read his Pulitzer prize-winning history of cancer, The Emperor of All Maladies, in the autumn of 2011, I had been a smoker for a quarter of a century and had no intention of stopping; 500 pages later, I went cold turkey. I didn’t know then that, 12 years later, the book would become relevant for a completely different reason.

Mukherjee, speaking from California, is gracious but not particularly surprised by the transformational effect his book had on my addiction. He is well aware of its impact on readers because he continues to receive emails from them. “The plaudits and prizes are great,” he says, “but there’s nothing more moving, and sort of deeply satisfying, than to wake up in the morning and read a random email saying: ‘Thank you for this book.’”

In December, a new edition of The Emperor of All Maladies was published, including 100 pages of new material, reflecting “the weight of knowledge and discovery and research” of the past 15 years. When I first read the book, I was amazed it didn’t already exist. The subject and its sweep, taking in everything from Galen’s theory of disease to the tobacco industry’s grotesque lies, seem to demand precisely the form Mukherjee gave it.

“The original version of Emperor was propelled by inevitability,” he says. “How on Earth could it be that this book didn’t exist? I’m not saying that as a humblebrag … When I would sit down in freezing Boston to write yet another paragraph, I would say to myself: ‘Why hasn’t someone done this?’ And it would astonish me.”

At the time, Mukherjee was a resident in internal medicine at Massachusetts general hospital. Born in New Delhi in 1970, he went to college in the US, studying biology at Stanford University and working on genes in the lab of the Nobel-winning biochemist Paul Berg (Mukherjee’s follow-up to The Emperor of All Maladies was The Gene: An Intimate History). As a Rhodes scholar, he traded California for Oxford, where he trained with Alain Townsend, who he describes as “one of the great immunologists of the world”. Together, they worked on a “very, very interesting puzzle around a cancer-causing virus called Epstein-Barr virus”. After this, “oncology seemed like a natural place for me to go”.

A tumour was found in Chris Power’s abdomen in February 2023; 18 months after receiving Car-T therapy, he is in remission

Although Mukherjee is a self-proclaimed “lab rat” and dedicates much of his time to research, he still does clinical work when he can. Indeed, interactions with patients helped formulate the book’s authoritative yet approachable style – one that embraces scientific complexity but never abandons less Stem-oriented readers. “When I treat patients, I’m not going to speak to them in the language and jargon of science. I’m going to speak to them in what I call natural language.”

Given the book’s breadth of reference – Mukherjee is comfortable drawing analogies between gene science and Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark, and quoting from Italo Calvino, Franz Kafka, Louise Glück and Audre Lorde – and its sophisticated structure, I’m not sure “natural language” does his writing justice.

Interweaving his own clinical experience with a history of cancer running from antiquity to the present day, he synthesises a vast amount of scientific, medical, political and cultural information; he describes a Persian queen ordering her Greek slave to perform a primitive mastectomy in 500BC, and the link between English cotton mills, advances in chemical dye making and the beginnings of chemotherapy, as well as the brutal operations of the Johns Hopkins surgeon – and cocaine and morphine addict – William Stewart Halsted, who, along with his disciples, “would rather evacuate the entire contents of the body than be faced with cancer recurrences”. Into all this, Mukherjee interlaces the alliance forged between Sidney Farber, a pathologist and the father of modern chemotherapy, and the socialite Mary Lasker, who together persuaded US president Richard Nixon to pour hundreds of millions of dollars into the supposed “war on cancer”.

Every story Mukherjee tells possesses its own narrative arc within the book’s larger one, braiding them together so the momentum never diminishes. Ever since I read The Emperor of All Maladies, I’ve often recommended it, but returning to the book, I realised I had forgotten just how good it is. It was No 84 on the New York Times’s 100 best books of the 21st century list: I think its position in The Observer’s own top 25 is more accurate.

This disease has been with us since the birth of humans and will be with us for many millennia to come

This disease has been with us since the birth of humans and will be with us for many millennia to come

What is it about cancer that singles it out for special consideration? What makes it the “emperor” among all the many other diseases that can strike us down? I suggest it might be luck, or timing, or the determination of Farber and Lasker. “I don’t think it has to do with them,” Mukherjee says, calling them products of cancer, not the shapers of its modern reputation. “This disease, that’s been with us since the birth of humans and will be with us for many millennia to come, is intrinsically linked to a certain sense of panic and fear. You don’t know where it’s going. You fundamentally don’t know how it’s going to behave or how it’s going to act. It arises from yourself. This is not an infection. It often arises because of nothing that you’ve done, not because you’ve exposed yourself to something, and sometimes when patients say: ‘Why did I get cancer?’, I have to very humbly say: ‘Well, I’m sorry, I don't know the answer. It was a genetic accident.’ And for human beings, that’s an answer that we don’t like to hear.”

He continues, recounting conversations he has had on oncology wards time and again. “‘I’m sorry it happened to you. I don’t know why. I can’t tell you what is going to happen next. But I can tell you that this is what we’ve done with patients before you and some fraction of it has worked,’” he says. “What an unsatisfactory way to answer someone’s question about life and death! And yet that’s the answer we have. I often say cancer’s a disease that brings out every personal uncertainty we have feared: ‘What will happen to me tomorrow?’ When you and I ask ourselves, hopefully cancer-free: ‘What’s going to happen to me tomorrow?’, we think along dozens of vectors. If we have children, we could say: ‘How will the children grow up and what impact will that have on my life?’ If you have financial success or difficulties, that’s another vector. What’s astonishing about cancer is that it essentially shrinks all those other vectors almost into nothingness, and it becomes the single vector by which you’re thinking about your life. ‘What is going to happen to me?’ Or: ‘How will I live my life now that I have a diagnosis of cancer?’ For the history of humanity, we’ve thought about our future in a fuzzy dimension governed by so many different angles: emotional, personal, familial, financial. And then you have a diagnosis of cancer, and all of that, suddenly, is put into the closet and locked up and there’s only one dimension. Our life becomes a unidimensional life.”

I recognise my own experience in Mukherjee’s words. On Christmas Day 2022, I felt a dull ache in my stomach, which I first thought might be the return of the gastritis I had experienced a couple of years before. By early February, I was rapidly losing weight and struggling to keep food and drink down. At the end of the month, a scan found a growth the size of a melon in my liver. I felt permanently seasick because the tumour was making the amount of calcium in my bloodstream spike. As my life rapidly became medicalised, I took The Emperor of All Maladies down from the shelf again, scanning the index for terms I encountered in my conversations with doctors.

Mukherjee describes himself as a ‘lab rat’

I continued to shrivel and the tumour to grow. By now, I could actually hold it. When I exerted myself, which by that stage included getting out of bed or crossing a room, I felt it throb (it had developed its own network of blood vessels). By mid-March, I was hospitalised, but an accurate diagnosis proved tricky. Two biopsies failed. The assumption was that I had a rare kind of sarcoma and a plan was formulated to remove my stomach (it turned out the lump had never been in my liver; as a consultant told me: “Everything’s packed in pretty tightly down there”).

But someone in a lab ran a test on a scrap of tumour that the last biopsy had taken and found I had lymphoma, a blood cancer. Within hours of this discovery, I was whisked in an ambulance from the Homerton University hospital in Hackney, my home for the previous three weeks, to St Bartholomew’s, a blood cancer centre of excellence.

Chemotherapy began that evening. Despite having lost 20kg (about 3st) and being fed through a tube, I almost immediately started to feel better. This is the opposite experience to many lymphoma patients. Usually, a lump is felt in the armpit, neck or groin before any symptoms have developed; in those cases, it’s the chemo that makes them feel rubbish. It eventually made me feel rubbish, too, but I was so unwell by this stage that just having a better chance of keeping down a meal was a huge improvement.

My cancer was a diffuse large B cell lymphoma, aggressive but often responsive to treatment. My chemotherapy lasted 18 weeks, after which I had a couple of inconclusive scans, followed by a surgical biopsy. Happy with the results of this, my haematologist told me I was in remission.

Ten days later, watching a play alone at the theatre, I almost passed out. I walked home, feeling too lightheaded to get on a bus. The next morning, I went to A&E and a new tumour was discovered, impinging on my stomach and causing heavy internal bleeding. I was told that several attempts to stop the bleeding had been made, all had failed, and that my situation “poses a significant threat to life”.

In the US, there has been almost a 30% decline in cancer mortality in the last 15 years. In the UK it’s 11%

In the US, there has been almost a 30% decline in cancer mortality in the last 15 years. In the UK it’s 11%

When, after a few days, it turned out the bleeding had stopped, I was put on emergency chemo and approved for Car (chimeric antigen receptor) T-cell therapy, an immunotherapy that is one of the main areas of focus in the expanded edition of The Emperor of All Maladies. In fact, Mukherjee identifies cancer immunology and its translation into new treatments, including Car T-cell, as “the single most important” advance in cancer therapy since the first edition of the book appeared. Biased as I am, I’d have to agree.

In Car T-cell therapy, a quantity of your blood is removed and spun in a centrifuge to separate the part of your immune system known as T-cells. I got my blood back, but my T-cells went to a lab in the Netherlands to be genetically engineered. A few weeks later, after undergoing a burst of harsh chemo to temporarily wipe out the new T-cells my body had produced – like emptying a room’s contents before painting it – the engineered T-cells were reintroduced into my body. A few weeks later, after undergoing a burst of harsh chemo to temporarily wipe out the new T-cells my body had produced – like emptying a room’s contents before painting it – the engineered T-cells were reintroduced into my body.

The reprogrammed T-cells were, in effect, under orders to hunt down and destroy specific protein receptors that stuck out, like pins from a pincushion, all over the surface of my tumours (of which, by then, I had four). The treatment had a roughly 50% chance of working and I won the coin toss: by day 28, a PET (positron emission tomography) scan showed that each of the dark masses had disappeared. A complete metabolic response. I was still in and out of hospital, developing sepsis twice because the treatment had all but destroyed my immune system (this is a cure that can kill), but at day 100, another PET scan confirmed the tumours hadn’t come back. Eighteen months later, I remain in remission.

The medical hedge that is remission – a judgment meaning that cancer isn’t necessarily absent, but certainly beneath the threshold of detection – encapsulates the way this disease, once it has entered your life, is difficult to ever banish entirely. Even if a treatment is as successful as could be hoped for, it’s very unlikely you will hear the word “cured”. Instead, you will be told, as I was, that your cancer is in remission: gone for now, but always with the possibility of return.

In The Emperor of All Maladies, too, Mukherjee tends to avoid the word “cure”. “I’m always uncomfortable using that word because 10 years later, all of a sudden, something that was dormant springs up again and then you have to bite your tongue.”

Are there any occasions on which he will use it?

“I’m getting increasingly comfortable,” he says, sounding anything but, “telling most patients with particular forms of breast cancer, the ‘triple positive forms’ – HER2, ER, PR-positive – that, if they have a great response, the tumour vanishes, it’s been surgically removed, they’ve had radiation therapy, then, following that, they’ve had potentially chemotherapy, potentially anti-hormonal therapy, and anti-HER2 therapy …” He takes a breath. “Look at the number of things I said. But all of that done, I think I’m getting comfortable saying to those patients that they really are cured.”

This procession of caveats is illustrative of the inherent difficulties of the field. The story of cancer treatment, individually and globally, has always been a combination of triumph and setback. In the case of the Car T-cell treatment that saved my life, it was thought that a host of cancers would fall before this new weapon, but while it has turned out to be “an incredibly important tool in the treatment of liquid cancers, such as lymphomas, leukaemias, and myeloma”, the story is very different in solid cancers.

In one of the book’s new chapters, Mukherjee describes studying a slide taken from a patient who died of ovarian cancer. The image’s “chilling feature” is “not the cancer but the immune cells. Far from infiltrating the tumour, they stood in a perfectly placid ring around the mass – like exhausted soldiers with dull fires lit around a citadel’s unbreachable moat.” Why? As is often the case in cancer treatment, no one currently knows.

Another problem with Car T-cell therapy is its extraordinary expense. My single dose, provided by the NHS but for which my doctors had to put my case to a national multidisciplinary panel, cost in the region of £300,000, and the lengthy hospital stay it required pushed the price even higher. It is even costlier in the US, where, Mukherjee writes, “prices rival the most expensive medical procedures in American medicine”.

This spurred him to develop Car T-cell therapy in India. By using Indian engineers, he has made it 10 to 20 times cheaper than the cost in the US. “If we can put a man on the moon,” he says, “we can bring Car T to India.”

The second time we talk, Mukherjee is back in New York. Behind him, the morning sun reflects off a whiteboard on which numbers are scrawled. His hair is boyishly dishevelled, as if he had fallen asleep at his desk. As he might well have done: in addition to his Car T project and overseeing a lab that has “four or five, maybe even six” drugs in active trials, he has launched Manas AI, a startup seeking to harness artificial intelligence to accelerate the discovery of new medicines, with an initial focus on cancer. His partner in the startup is Reid Hoffman, the billionaire co-founder of LinkedIn. The project, Mukherjee says, has already harvested “amazing new data for new cancers and other diseases”, adding: “AI can design new chemicals that humans can’t easily design.” It’s refreshing to have a conversation involving AI that isn’t about humanity’s destruction or obsolescence.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

All this work is keeping Mukherjee not only from the clinic, but also from the writing desk. He says The Gene “well might have an update”, and he doesn’t rule out making another one to The Emperor of All Maladies down the line (he is happier with the future-proofing of his third book, 2022’s The Song of the Cell). But it doesn’t seem a new book is coming any time soon.

The Emperor of All Maladies is full of examples of cancer consuming not just those for whom treatment doesn’t work, or didn’t yet exist, but also the doctors and scientists who devote their lives to fighting it. Does Mukherjee, who has two daughters (he divorced from their mother, the artist Sarah Sze, last year), ever get away from cancer?

“I spend time away by reading. I spend time away by thinking about the wider world, which is a particularly challenging thing to do; these recent times have been reminders of the fact that we are in such a challenging place in our political lives, in our public lives, that we need to think about what to do. I think that there is a deep resistance to science and scientific thinking.”

His attempt to talk about something other than his life’s work lasts all of 10 seconds, but perhaps that’s only to be expected of a man who is both a pioneer in cancer treatment and in its chronicling: a double role that leaves little room for anything else.

The dream, when it comes to cancer, both for individual patients and society, is that we become free of it. Launched in the early 1970s, the “war on cancer” envisaged a world from which the disease had been eradicated: a complete metabolic response of the kind I experienced in the summer of 2024, only species-wide.

The idea quickly foundered, as researchers became overwhelmed by the sheer number of cancers, and the diversity of spread and resistance within each sub-category. Mukherjee cites reasons for optimism; “In the United States, there’s been a marked decline in cancer mortality, almost a 30% decline in the last 10 to 15 years. That’s enormous progress.” (It’s a less impressive 11% in the UK.) But, he says, “the idea that we would eliminate it completely from human lives is, I think, absurd”.

And then he says something I’ve been returning to ever since. “Cancer’s end is not conceivable,” he tells me. “Cancer is part of who we are.” It’s an idea I find chilling, but also reassuring – perhaps because, in my case, my body produced both the poison and its antidote.

The new edition of The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer is published by 4th Estate. To order a copy for £11.69 go to the observershop.co.uk. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Eva Vermandel, Alamy