Somewhere in the Australian outback, young women in overalls dance in unison. Against a background of red earth, they twirl and stomp their desert boots. It’s a performance worthy of a thousand clicks.

Online, an unlikely workforce has found an audience: Australia’s fly-in, fly-out (Fifo) miners.

These labourers fly thousands of miles across barren land to extract iron ore and gold in Western Australia, or dig for coal deep underground in Queensland. Two weeks of 12-hour days in the scorching sun and prison-like campsites. But then? Two weeks off – with thousands of dollars to spend. Rinse and repeat.

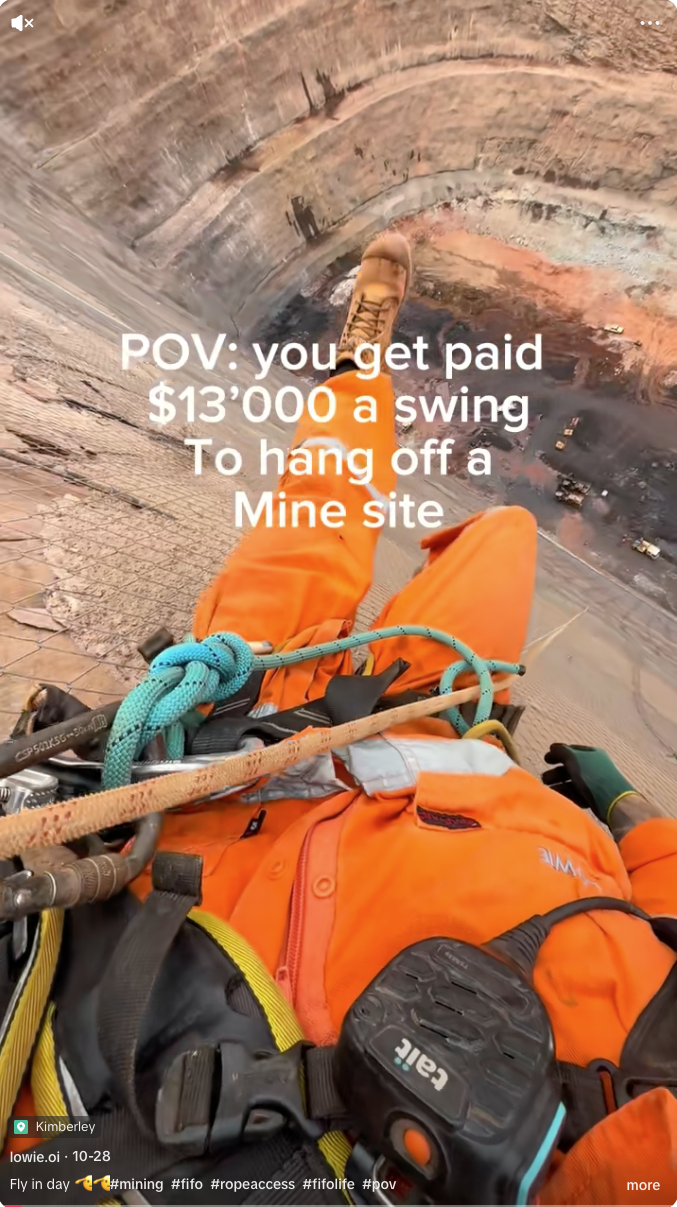

This double life has been the brutal reality of Australian mining for decades. But recently it has become an aspirational lifestyle among gen Z. On TikTok, “Fifo influencers” in helmets and hi-vis gear post “a day in the life” reels in which they operate machinery, count wads of cash and boast six-figure salaries. A year in a mine means a downpayment on a mortgage, they insist.

‘They ruined my mental health. I’d sit in a machine for hours and wish I could be back home’

‘They ruined my mental health. I’d sit in a machine for hours and wish I could be back home’

Georgia, miner

It’s attracting a wave of young Europeans on working holiday visas – available to UK as well as some EU citizens – fleeing stagnant wages and a cost-of-living crisis. But it isn’t all it seems. The Observer spoke with 10 Fifo workers who say influencers are glamorising the job and selling the fantasy of a get-rich-quick adventure.

“Young people are coming to Perth expecting the streets to be paved with gold,” says Steve Howe from Penzance, Cornwall, who has done Fifo for three years. “But it’s not the fun and games that you see on TikTok.”

The #Fifo boom

Georgia, 25, was scrolling at home in the Irish city of Limerick when she first heard the term “Fifo”. The person on the screen, who was about her age, spoke of earning thousands a week, enjoying half the month off, and staying in all-inclusive accommodation during the other half.

“I realised that this could be a great way to make money,” says Georgia, who had recently graduated from her master’s degree with thousands of euros in student debt.

Visa stamped, Georgia boarded a flight to Western Australia in January 2024, in search of the Fifo fantasy.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

More than 80,000 posts appear when you search “#Fifo” on TikTok. The first 500 or so – ordered algorithmically – have amassed more than 148m views. The majority have emerged since 2022, and #Fifo searches in the UK are up tenfold in two years, data from TikTok’s Creative Centre reveals. Almost 60% of viewers are aged 18 to 24.

Working holiday visa data aligns with this timeline. During the 12 months to June 2024, the number of second applications granted in mining almost tripled from the year before.

But why did TikTok erupt?

In 2021, Western Australia’s mining sector faced a 40,000 skilled worker shortfall. Soaring demand for iron ore from Chinese steel mills, and for the lithium needed to build electric vehicle batteries, have resulted in more mining projects. The supply of jobs has risen accordingly. Meanwhile, the pandemic squeezed labour. So mining companies went on a hiring blitz. As a result, average annual earnings have shot up 20% since 2021, hitting more than £82,000 in May this year.

This all coincided with Europe’s cost-of-living crisis, caused by decades of high inflation and years of stagnant wages. The median starting salary at the UK’s leading graduate employers was £30,000 in 2021 – a figure that hadn’t changed for seven years.

More miners boasting about their payslips and savings came at just the right time to gain traction.

Cashing in on the Fifo gold rush

When Georgia arrived in Perth, it became apparent that landing a job wouldn’t be easy. Surging interest from foreigners means competition has become fierce and openings attract thousands of candidates.

Fifo content creators are cashing in on this demand. With more than 1.14 million followers between them, the four largest TikTok accounts hawk résumés and guides to get a job. One creator advertises a WhatsApp call for £70 and a list of phone numbers for £19.99. Another sells a CV for £224. One offers an “elite mentorship” package for about £950.

“Kids are handing this money over with some belief that it’s going to be an easy life, they’re going to make an absolute fortune, and they’re going to be able to buy a house,” says Steve.

In reality, young Europeans on working holiday visas often lack the relevant skillsets and authorisation for lucrative mining jobs. Some get roles cleaning campsites or driving trucks. Even skilled workers often find their qualifications don’t meet Australia’s regulations.

Some of these TikTok accounts belong to so-called “training” companies that sell courses to learn how to drive dump trucks, carts or excavators, in just a few hours. These are the golden tickets to get a job, they claim, and sell for hundreds of pounds.

“These people aren’t qualified to do that. It’s a total scam, it’s preying on vulnerable people who don’t know any better,” says Bailey, a 20-year-old Fifo worker from Western Australia.

Each year, a few thousand foreigners will strike gold. Georgia was one of them. Despite the odds, she found a gig operating heavy machinery in the Goldfields region on a starting salary of £50,000 that could go up to £110,000. “I was very lucky,” she admits.

Taunts and targeted violence

But once she flew in, things looked very different from what she had seen online.

The campsite was mostly men – as is 80% of Australia’s mining workforce. Throughout her year at the site, sexual harassment and bullying was rife, she claims. Georgia detailed her allegations in a complaint to the mining regulator seen by The Observer.

Three men in their 50s would beg for her towels after showering. They consistently threatened to enter her bedroom “to do what they wanted to [me]”, she writes in the complaint, and would knock on her door at night. They repeatedly asked for oral sex, and ostracised her once she refused, instructing new starters not to speak to her.

“They absolutely ruined my mental health,” she writes. “I began crying all the time at work. I’d sit in a machine for hours and wish that I could be back home with my family,” she says.

The stress wreaked havoc on her body. Hives covered her skin, and she once fainted on the job. She eventually took time off.

It’s estimated that 74% of women in Fifo mining have experienced sexual harassment, according to a 2018 report by the human rights commission.

The chair of a 2022 parliamentary inquiry into sexual harassment in mining wrote: “I was shocked and appalled well beyond expectation by the size and depth of the problem.”

The inquiry’s report found that “taunts, attacks and targeted violence” against women are widespread but “generally accepted or overlooked”.

Despite the findings, the problem persists. Rio Tinto, the world’s second-largest mining company, revealed eight allegations of rape or attempted rape in 2024, up from five in 2021, even though only a fifth of employees completed the survey.

In reality, these figures are just the “tip of the iceberg”, says JGA Saddler lawyer Joshua Aylward, who filed two class-action lawsuits against mining giants BHP and Rio Tinto last December, alleging systemic sexual harassment at mine sites.

He expects “thousands of women” will come forward to join the class action, adding that he’s already spoken with about 100 women who report experiencing assault, ranging from unwanted touching to rape.

In the suit against Rio, the lead applicant claims that between 2019 and 2022 she received unwanted sexually explicit images, texts and videos from a man on site, was physically groped, and witnessed jokes about rape and incest, court documents obtained by The Observer allege. After she reported an incident, the applicant claims one of the perpetrators lodged a complaint against her, alleging she had used profanities, and was prevented from returning to work for being “too upset”.

Among the lead applicant’s allegations against BHP, she describes an incident when a worker urinated on her, called her a “slut” and to “fuck off out of the industry”, court documents show. A week after reporting the incident, the applicant says she was dismissed.

“There’s a huge culture in mining where you don’t report these things, because bad things happen when you do,” Aylward says.

“We apologise to anyone who has ever experienced any form of sexual harassment at BHP,” a spokesperson said, adding that the company has rolled out behaviour training, invested in campsite security and improved its reporting system.

Rio Tinto said: “We do not tolerate any form of sexual harassment or sex-based harassment. We take all concerns about workplace safety, culture and breaches of our values, or our code of conduct extremely seriously.” The company encouraged employees to use a confidential reporting system.

Yet Aylward says it’s “common practice” to use non-disclosure agreements to “shut [women] up” and downsize the problem. BHP says it ceased using NDAs for sexual harassment allegations in 2019, and a Rio Tinto spokesperson has said it “will not enter or enforce any historic confidentiality terms that prevent employees from discussing their personal experiences”.

In Georgia’s complaint to the regulator, which is unrelated to any claims against Rio or BHP, she claims there was not only no accountability on site, but managers were often perpetrators. She describes an incident when a supervisor barricaded her in an office and denied her access to the bathroom. She also witnessed a young girl be harassed for sex by two supervisors, including physical groping.

When Georgia reported “daily” bullying from the men who had requested oral sex, the safety officer told her to “get used to it”. It took three months of complaints for one of the men to be reprimanded – another was later fired for exposing himself to a woman while she was operating machinery.

‘A man’s world’

Male Fifo workers also told The Observer they’ve struggled with the culture and lifestyle.

“If you’re young and you want to save money, it’s hard to beat,” says Tim, from Germany, who was backpacking when he got “very lucky” and landed a Fifo in 2023, aged 27. “But it’s definitely not as simple as it’s made out to be online.”

The high wages “reflect your ability to take punishment” rather than your skills, he says, recoiling at the memory of 12-hour days in “brutal” heat nearing 50C. “The harsh working conditions foster this extremely masculine, macho culture,” he adds. “It’s a man’s world out there.”

One supervisor threatened him with physical violence. A team member who appeared to be on drugs assaulted him. Some workers challenged him to a fist fight. “Vile, disgusting” things were said about indigenous Australians on a daily basis.

“It can be a very toxic environment,” says Sam, an Australian with a similar tale of machoism, misogyny and racism from his Fifo stint back in 2019. If a single woman joined the camp, it would be like “sharks in the water”.

The camp also looked and felt like a prison, he says. “You can go and walk off into the desert if you want, but you’ll die before you get anywhere.” Sam’s mental health deteriorated fast. He’d call his parents twice a day, “just to hear somebody’s voice to feel like I wasn’t completely alone”. About six months into the job, Sam was looking out of the window at a mining truck when he began to fantasise about throwing himself under it. After that, he quit.

“There is not a lot of mental health support, and I saw quite a lot of the younger guys struggling,” says Steve, who says one man hanged himself at his site.

‘Golden handcuffs’

On Georgia’s TikTok – in which she dances on red earth, smiles behind the wheel of a dump truck, and travels around Asia – life’s good. It’s only when sifting through the comments section that the fantasy begins to crumble. “Useless,” one user writes. “Camp call girls,” says another.

Despite the brutal man’s world offline, since relocating to a site where she feels safe, she’s decided to stay another year.

“Without this job, I would never afford to buy a house in Ireland,” she says.

Tim often meets men who want to leave Fifo after years in the industry, but with private school fees and car loans to pay, they can’t afford to quit.

“They’re never getting out of the mines. Happens all the time,” he says. “The golden handcuffs.”

Photograph by Carla Gottgens/Bloomberg via Getty Images, TikTok