In Tehran, the authorities are unable to wash away the blood staining the pavements. The morgues overflow with corpses; so full that rows of black body bags line the grounds outside or lie piled in refrigerated lorries. Injured protesters have been dragged from hospital beds by security forces and arrested. Officials sometimes refuse to return bodies of demonstrators to grieving families – fearing funerals will spark more dissent.

Iran has witnessed a level of bloodshed not seen since the 1979 revolution that brought its theocratic regime to power. What began as unrest over the rising cost of living quickly morphed into calls for the fall of the regime before being met with a hail of machine-gun fire.

The crackdown that swept the entire country in response to the protests was swift, bloody and unfolded at a scale designed to terrify the population into submission. Iranian human rights groups based abroad have been overwhelmed as they attempted to track the wave of killings. The US-based group Human Rights Activists in Iran (HRAI) recorded 3,090 people killed, with a further 3,882 cases “under review”.

A man stands in the wreckage of a bus in Tehran’s Sadeghieh Square that was burned by protesters demonstrating against economic hardship

Iran Human Rights (IHR), based in Norway, said the Iranian health ministry registered the deaths of at least 3,379 protesters within a five-day span, while evidence of 3,428 dead since the protests began is “an absolute minimum”, IHR said, amid fears that the true toll could be many times higher. Even supreme leader Ali Khamenei delcared “several thousands” were killed, while an Iranian official told Reuters they believe 2,000 people were killed.

US President Donald Trump, who had threatened to intervene if Iran killed protesters, appeared to back away, thanking the Iranian regime for cancelling “over 800,” hangings scheduled last week. But hardline senior cleric Ahmad Khatami on Friday demanded that “armed hypocrites should be put to death”.

The mounting death toll came alongside horrifying accounts: a group of young protesters trapped in fires engulfing the Rasht bazaar who surrendered to security forces, only to be shot dead. Witnesses told IHR that wounded protesters on the streets and even in hospitals were “finished off” by security forces.

‘They have had to put the bodies in industrial containers. They don’t have the space for all of them‘

‘They have had to put the bodies in industrial containers. They don’t have the space for all of them‘

Yasser Oorashi, Iranian exile

But those accounts are emerging from behind a wall of silence. The authorities cut the internet on the evening of 8 January, sealing off Iran from the outside world – allowing security forces to kill in the dark. “The mass killings started right after the internet blackout,” said Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam, IHR’s founder.

Based on interviews with human rights groups, Iranians in touch with contacts through satellite links, and reporting from the border, The Observer has tried to piece together what happened in the days after the blackout began.

Exiled crown prince Reza Pahlavi

Iran’s streets v old leaders

Like many uprisings, this one began with a protest about the cost of living. In late December, traders in Tehran’s bazaar closed their shops and began demonstrations over the state of the economy. For the traders, the rapid collapse of the Iranian rial and soaring inflation had made doing business all but impossible. They were soon joined by others eager to vent their anger at the authorities.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Pockets of protests spread through towns and then cities across Iran over the next 10 days, as discontent with the economy quickly became demands for something much larger: chants for the overthrow of Khamenei and the end of his regime.

Most of those taking to the streets were younger than the 47-year-old regime that Khamenei spearheads – they have known nothing other than rule by an ageing ayatollah. Initially, the Iranian government said that people had a right to protest and it was ready to listen to their demands about the cost of living. Others, including Khamenei, aimed their ire at those they accused of rioting. The head of Iran’s judiciary, Gholamhossein Mohseni-Ejei, warned “this time there will be no mercy for the rioters”, in an ominous post on X.

Donald Trump voiced his support for the protesters on 2 January, when rights groups put the death toll in single digits. “If Iran shots [sic] and violently kills peaceful protesters, which is their custom, the United States of America will come to their rescue,” the US president wrote. “We are locked and loaded and ready to go.”

For a brief moment, it appeared Trump’s threats had cornered the Iranian regime: officials were desperate to end the mounting protests, but were fearful of being seen to crack down on them in case they triggered an American attack.

But in a harbinger of the violence to come, police special forces, along with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), attacked a protest in Malekshahi in western Iran, near the border with Iraq, killing several demonstrators, before storming a hospital an hour away in the city of Ilam, where the wounded were taken. They fired shotguns and teargas into the grounds, beat medics inside the hospital and dragged injured protesters from their beds under arrest.

A woman attends a funeral ceremony held for more than 100 security personnel alleged to have been killed during nationwide unrest

Exiled Iranian doctor Yasser Qorashi got a call from a medic friend working in the Ilam hospital, who described fearfully sheltering in his ward during the attack. “At that point, it was just fear about why they attacked the hospital. No one was aware of how far these protests would go,” Qorashi said.

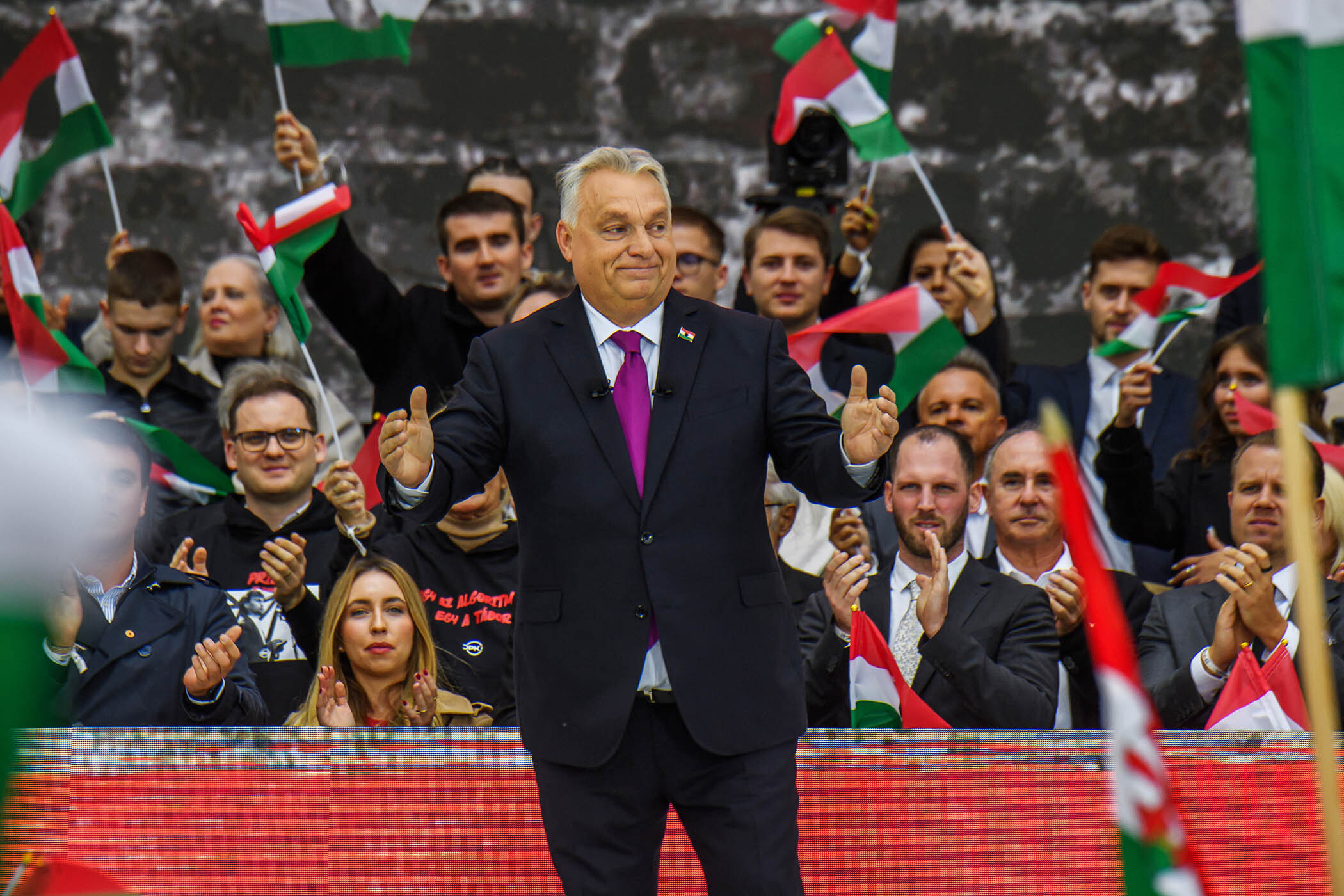

The protests grew, buoyed by the exiled crown prince, Reza Pahlavi, son of the unpopular shah deposed by the 1979 uprising. Pahlavi began issuing instructions to the demonstrators, attempting to position himself as their leader.

Some in Iran chanted for his return, such as a demonstrator in the northern coastal city of Rasht named Meisam, but he told The Observer that Pahlavi was merely a symbol of a better time – he did not want the monarchy back.

People had been too tolerant with notions of reforming the regime, Meisam said, and he was ready to die to see its end. “A lot of people I talk to these days who are joining the protests have reached that point in their lives too,” he added.

Everything changed not long after he hung up the phone. As thousands of protesters filled streets in towns and cities across Iran on 8 January, the regime abruptly severed its internet connection to the outside world.

“No one expected the turnout would be so high until that night,” said Qorashi. “The regime really started killing from that moment.” The regime aimed its full force against the demonstrators, who had no way of knowing the scale of the violence inflicted on neighbouring towns and cities.

In an instant, Qorashi’s WhatsApp calls to his medic friend in Ilam rang off. Messages to Meisam in Rasht sat undelivered. “After the internet blackout, things exploded,” Qorashi said sadly.

Killings in the dark

Since then the trickle of information that cuts through the silence comes only from the medics and protesters who know someone with a Starlink satellite internet terminal. Another of Qorashi’s contacts, a doctor in western Iran, stayed overnight with a friend who he knew had access to Starlink and managed a five-minute call during which he expressed “shock at the brutality”, Qorashi said.

In Norway, Amiry-Moghaddam watched as a few of his contacts came online just long enough to recount the horror they were witnessing. “This is why documentation is so difficult now – the information is coming, but at a delay,” he said. Nevertheless, he began to notice a pattern: killings on a scale unknown even in Iran’s recent history.

Qorashi had last spoken to one forensic doctor in Tehran before the internet cut, when he estimated there were 200 bodies in the morgues linked to three Tehran hospitals. Five days later, the same doctor came back online long enough to describe a nightmare scenario: the first thing he told Qorashi was he could still see “blood in the streets”, during his journey to work at the hospital. He estimated there were more than 3,000 in the same Tehran morgues at that time, with another 1,500 in the central city of Isfahan. “They’ve had to put the bodies in industrial containers. They don’t have space for all of them,” Qorashi said. His voice shook as he recounted what he heard.

Iranians demonstrate at an anti-government protest in Tehran in January 2025

Accounts and videos shared by human rights groups showed security forces positioned on balconies or rooftops to shoot into crowds of protesters below. In some cases, they fired metal pellets that can blind; one Tehran eye hospital reported an influx of 500 patients. But two doctors who spoke to Qorashi, including the forensic specialist in the capital, described seeing corpses shot in the head and torso with live ammunition. IHR said it had evidence of security forces using mounted machine guns to attack protesters.

“On the first night, most of the injuries were from the pellet guns,” Qorashi said. “But after that, nearly all the casualties were from assault weapons: they are using heavy machine guns. One doctor I spoke with told me in some cases the whole face was unrecognisable. The amount of ammunition shocked him. It seems they had a shoot-to-kill order – most of the bodies he saw were shot in the torso or head.”

Regime channels broadcast freely during the blackout, and one linked to the IRGC even showed an interview with a doctor standing among rows of body bags in a morgue. He described how demonstrators had been killed with shots to the head, from buckshot or bullets. This was used to bolster the regime’s narrative that it was foreign agitators among the protesters who slaughtered them, not security forces.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, greets supporters in Tehran on 17 January

Members of the latter also swept into hospitals and morgues as the death toll soared, medics told Qorashi. In forensic facilities, they inspected doctors’ phones as they left to ensure they had not surreptitiously taken photos of the masses of bodies. The number of dead could be higher still; doctors described how families had identified their loved ones at hospitals and taken the bodies with them to avoid handing them to officials at state morgues, fearing the authorities might bury them in an unknown location or simply refuse to return the corpse.

The Dadban legal advocacy group said it had received reports of families pressured by the authorities to say their deceased loved one was a member of the state-backed Basij militia, or file complaints against unknown assailants in order to receive their body. Officials also demanded exorbitant sums of money to return bodies – amounts far beyond what most can afford. “In some cases, families have been asked to pay between 700m tomans [£4,165] and 1bn tomans to receive the body of their murdered loved one,” said a member of Dadban, who asked not to be named. The authorities, he added, had “transported the bodies in degrading ways – in some cases, multiple corpses were stacked in a van or transported in sacks”.The Iranian regime could still kill yet more, with thousands at risk from another deadly form of state violence: both HRAI and IHR warn that more than 20,000 people were arrested, amid fears they will face charges that carry the death penalty.

Mohseni-Ejei has threatened swift trials and no mercy for anyone arrested at demonstrations, including during a visit to a detention centre holding protesters last week. “If it gets late, two months, three months later, it doesn’t have the same effect. If we want to do something, we have to do that fast,” he told Iranian state TV.

The beginning of the end or the end of the beginning?

Seated in the Oval Office on Wednesday, Trump told reporters: “We’ve been told that the killing in Iran is stopping. It’s stopped, it’s stopping… and there’s no plan for executions.”

Trump’s proclamations may have granted the thousands of Iranian protesters in detention temporary reprieve but their future remains uncertain.

The case of 26-year-old Erfan Soltani made this plain: after the clothes shop owner was arrested at his home in a small town near Tehran on 8 January, his family were told he would be the first protester to hang. His execution was set for a week later with no chance of appeal.

Then Iranian officials appeared to back away from their threats to Soltani’s life after an international outcry. A spokesperson for the judiciary told state media he would remain imprisoned, seemingly on lesser charges – but still with no way to mount a defence or gain his freedom.

Arina Moradi of the Hengaw Organization for Human Rights, which has tracked Soltani's case and others like it, said the threat to hang any demonstrator shows how the Iranian regime is wielding executions to punish dissent: “This is a message to protesters and to the people of Iran, to show them how brutal and serious the system is when it comes to demonstrations,” she said. Some fear the Iranian regime could dare to repeat infamous mass executions it conducted within its prisons in 1988, when thousands were hanged.

Erfan Soltani’s family were told he would be the first protester to hang

Thousands could still be put to death after Khamenei accused protestors of acting as foreign agents, and Tehran’s prosecutor said many have already been indicted. “We do not want to take the country to war,” Khamenei declared in remarks aired on state television. But, he added, “the Iranian nation should break the backs of the seditionists.”

Amid the blackout, scattered videos began to emerge of life on the ground in Iran; rows of police vans and security forces lining the streets in an effort to show the regime is in total control – and that the protests are not just deadly, but futile. The crackdown has done nothing to curb the broad discontent that fuelled it, even from sectors of society traditionally considered supportive of the regime. After prayers and at funerals, what few videos make it online show people cursing Khamenei as they bury their dead – exactly as his regime fears. There are small signs of the Iranian internet slowly flickering back to life, and landlines can now call out of the country. But as a shell-shocked population learns the scale of the bloodshed the authorities are willing to mete out against their own people, the regime’s new bargain with its people is becoming clear: it is capable only of brutally repressing the population, but not solving the punishing cost of living, and the government mismanagement and corruption that have made life unbearable for most Iranians. So far, the regime has emerged in control of the streets, but politically weakened – even some who previously favoured reforms quickly reconsidered there views after the wave of violence.

What has remained, even for those who fled Iran, was fear. At the freezing Kapiköy border crossing into Turkey, Iranians dragged suitcases on the wet ground that runs between snow-covered peaks.

Many were too scared to talk. “We don’t know anything about anything – we couldn’t even call our next-door neighbour,” said one middle-aged woman. A nearby man heard the ping of a message on his phone, and took it out of his pocket before displaying the text he had just received: a warning from the IRGC’s intelligence arm encouraging Iranian citizen s to turn in protesters, who it has labelled “Zionist and American terrorists, thousands of whom have been neutralised so far.”

One woman shouted in anger: “We want to live – we can't risk our lives. I will just tell you this: they are killing everyone. Everyone.”

Photographs by Henry Nicholls/AFP/Getty Images, Atta Kenare/AFP via Getty Images, AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein, Stringer/Getty Images, AP, Iranian Leader Press Office/Anadolu via Getty Images