Since Donald Trump re-entered the White House nearly a year ago, European governments have tried to convince themselves that their alliance with the US can survive.

They have swallowed tariffs and humiliations, offered trinkets and baubles (gold bars from the Swiss, a second state visit from the British), laid on the flattery and refused to whisper a single note of criticism.

But while there was a private acceptance that the US might no longer be an ally, it was not until the events of the past few weeks that key figures in European governments finally came to the conclusion that a Trump-led United States is actually now an adversary.

The publication in December of the US national security strategy, which claimed Europe faces “civilisational erasure” and pledged support for far-right “patriotic” parties, laid it out in black and white. Trump’s insistence the US will own Greenland, “whether they like it or not”, made it impossible to ignore.

Over the past few days, European leaders have carefully spoken about the importance of the Nato alliance and defended the sovereignty of Greenland and Denmark. Until now, though, they have all been wary of naming the aggressor.

That has to change. Trump’s announcement on Saturday that eight European nations, including the UK, would be hit with tariffs for having the temerity to stand up for the western alliance, has to be the moment when Europe’s leaders publicly and unequivocally break with the US president.

Away from the headlines, Europe is already preparing for a world where the US isn’t by its side. A Nato alliance without the US is now being actively considered. Last week the EU commissioner for defence, Andrius Kubilius, tried to flesh out what this would look like, urging his colleagues to consider how they should replace the 100,000 US troops stationed in Europe.

He proposed the creation of a European security council, which would coordinate any unified military action, reminding Sweden’s national defence conference that the EU has its own version of Nato’s article 5 – namely, he said, the “obligation of mutual assistance for member states, which face an armed aggression”.

When that was first written, you doubt Europe had the US in mind as the potential aggressor. “We have to start thinking about a non-US Nato,” said Fabrice Pothier, a former director of policy planning at Nato.

“It is increasingly sinking in that we should start planning and building defence arrangements that cannot replicate what the US brings but would at least be good enough.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

In much the same way as Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 encouraged Sweden and Finland to join Nato, the US wish to conquer part of Europe has spurred European nations to consider things previously deemed unthinkable.

The reliance on American technology, most notably Microsoft, which powers the infrastructure in numerous European governments, is also now up for debate. Last autumn the international criminal court announced it would replace Microsoft Office with German software, amid fears that US sanctions could lead to the tech giant withdrawing its services. Now some European governments are considering the same question.

For many Europeans, it is the words more than the actions that have shocked them the most. In an interview with CNN’s Jake Tapper this month, Trump’s deputy chief of staff, Stephen Miller, starkly laid out the administration’s new worldview.

“We live in a world in which you can talk all you want about international niceties and everything else, but we live in a world, in the real world that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power.”

Bronwen Maddox, director of Chatham House, said: “This is such a profound change. It’s not an exaggeration to call it the end of the western alliance.” Over the past year there had been, she added, “a great desire to hope all this goes away”. But after the publication of the US national security strategy, that had changed. “It was a pivotal moment, setting down formally the disdain for Europe. It’s an astonishing document,” said Maddox.

There is still a hope that the US will change course. The optimists point to midterms in November that will probably see the Republicans lose control of the House of Representatives and the race begin for his successor. If a Democrat wins in 2028, the alliance can be rebuilt.

Maddox isn’t so optimistic. The elections are not just a test of Trump’s unpopularity, but also whether elections in the US can still be considered free and fair. They will also, she said, answer a more existential question. “What is America and what are they choosing to become? And that goes way beyond Trump.”

We may not like the answer.

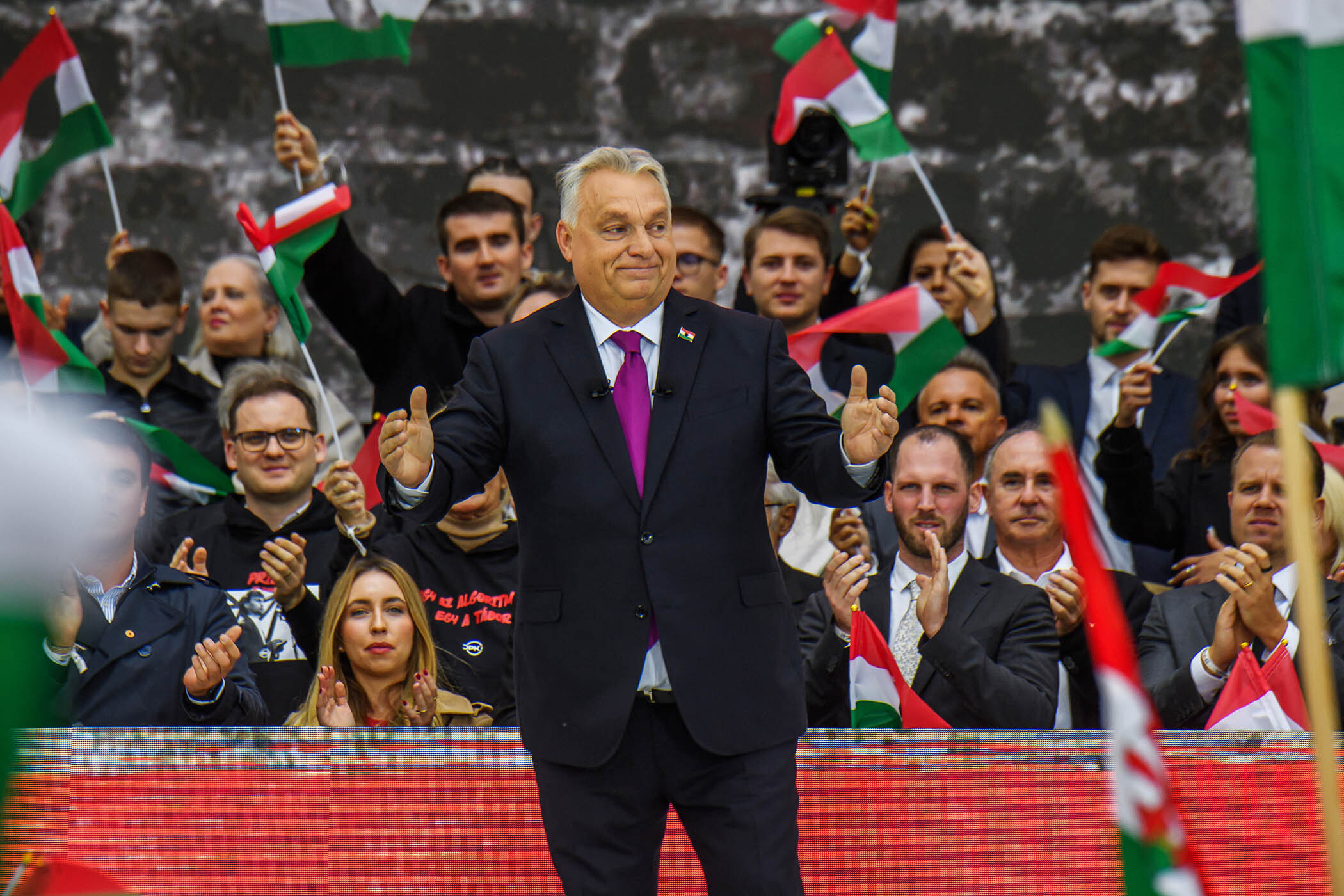

Photograph by Omar Havana/Getty Images