It was like a therapy session, or an AA meeting, but we called it a Winfield House Dialogue. Winfield House: the official residence in London of the US ambassador to the UK. In 2016, when this particular dialogue took place, I was that ambassador. Twenty members of our Young Leaders UK group – about 2,000 young British professionals from business, government and non-profits – were in attendance, having got their coveted places by writing a three-sentence explanation of what they hoped to get from the session: a conversation with our guest, the Rev Jesse Jackson.

Jackson, who has died aged 84, was a baptist minister and one of the most important leaders of the civil rights movement in the years after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. His two presidential runs helped lay the groundwork for the election of the first Black president, Barack Obama.

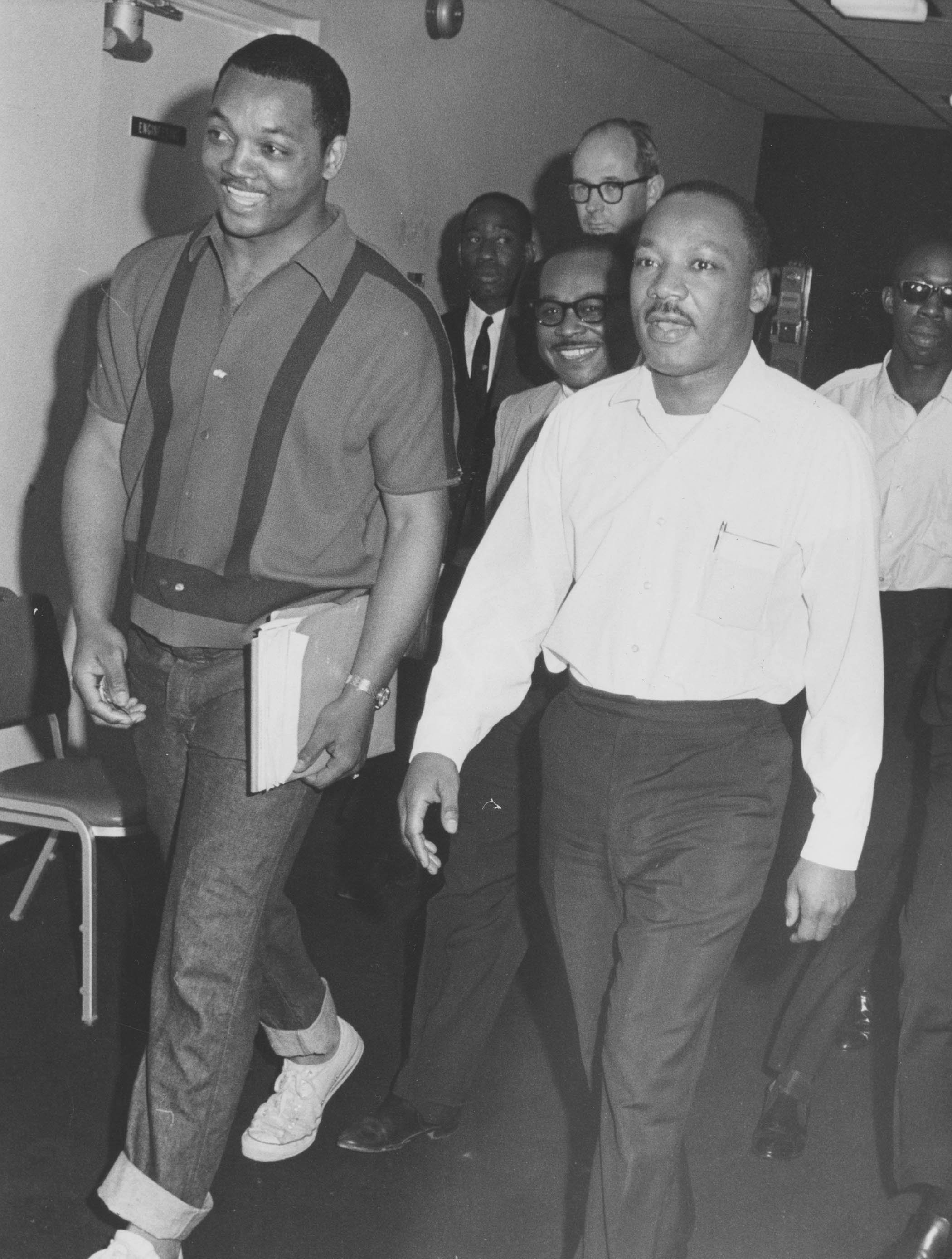

I welcomed Jackson, sat down in a chair beside him in the circle and passed around a framed black-and-white photograph of a young Jesse Jackson walking with Dr King, so everyone could recognise that this larger-than-life figure was once a young person like them. I keep that photo on my desk now. He had given this to me when I first met him, on my second day on the job, in 2013, at an event at the American embassy in London marking the 50th anniversary of King’s “I have a dream” speech.

Martin Luther King, Jr. and Jesse Jackson in Cleveland, 1967

Now, three years later, Jackson spoke about what he had been thinking as that photograph was taken – the uncertainty of the moment, the risks they knew they were taking and the choices he made in those days of the battle for civil rights in the 1960s. Then, as we always did, we opened it up for discussion and encouraged people to share their hopes and fears and struggles.

It was a diverse gathering: there was only one white male participant other than me. We had a lively discussion and nearly everyone had a chance to share with and learn from Jackson.

“We have time for one more question,” I called out.

Four hands shot up. Three had already asked one and the only first-time questioner was the other white guy.

“I’m Christopher and I studied at Cambridge University and am now in financial services,” he said.

I wondered where this was going. I knew from the bios of all the other participants that others were more actively engaged in the civil rights fights of our time (LGBT, disability rights, immigration) and I hoped my team hadn’t let someone slip in who thought this was a breakfast briefing on the economy.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“I have a practical question, Reverend Jackson. What advice can you give me for what to say when a superior in the workplace says something racist or sexist? This happens more than it should in my world and I am embarrassed to say that I don’t have a very good track record of speaking up. I want to get better at this.”

Jackson nodded as he listened to the question. “Christopher, you need to do three things when your boss or someone in power says something like that,” he said. “And you have to do them in this order. The first thing you need to do is ask yourself if you ever say anything like that. Maybe this person is being racist and you may not say racist things – but maybe you say things that are sexist, or that sound sexist to those around you. This first step doesn’t involve saying anything out loud. It’s a conversation you need to have with yourself. So do that.

“Second, after the meeting is done and after the boss is gone, you should go up to the person or the people in that meeting that you think were offended by the comment and tell them that you noticed. You don’t have to say anything clever or profound. Just say you noticed. I can tell you from experience how much that means just to know you are not alone.”

Now, number three was what I had been waiting for. But I would need to wait longer.

“Next, repeat steps one and two. Over and over again. Keep asking yourself if you are offending or isolating or disempowering others, and keep letting your coworkers and colleagues know that you noticed the offence. If you keep doing this then maybe, just maybe, you can get to number three – which is saying something out loud to the boss. You will know when the right time is.

“You see, if you jump right to number three, that’s too hard. You will chicken out and feel bad and won’t take the time to do the first two steps.”

Jackson asked if we could all pose for a team photo – while I had a stern conversation with myself about judging an Oxbridge grad in financial services by his looks and manner. Jackson asked if I would stand next to him, which posed a logistical problem. He was a big man, a great athlete in college, and considerably taller than I am. If we were both in the back row I would be obscured, and if he were in the front row with me we’d have the opposite problem. He solved it by suggesting everyone stand around in a semi-circle and he and I would kneel in front.

Our embassy photographer snapped four shots and the standing members milled around and began to exchange contact information. Jackson put his hand on my shoulder: “Son, you are going to have to help me.”

“Absolutely, anything. What can I do? The embassy will be glad –”

“No, not that kind of help. I’m an old man now. Kneeling isn’t hard, but getting up from kneeling is very hard. I need you to lift me up.”

He pushed down on my shoulder and I pushed up with my legs and wrapped my arm around his wide shoulders until he towered above me again.

Photograph by Astrid Riecken/Getty Images, Cleveland Public Library Photographic Collection