I was on a Teams call at work when Sandra’s name came up on my phone. There was nothing particularly unusual about that. Sandra was my brother’s key worker from Haringey council, so it would usually be something to do with the stuff of his life – a court appearance, an unpaid electricity bill, a housing issue. I stayed on the work call.

Moments later, my phone started to transcribe the voicemail Sandra was leaving. The words “so, so sorry” came up on the screen. Heart pounding, I called back. Sandra answered straight away.

“Karl, I just wanted to tell you how very, very sorry I am, and to send you my condolences at the sad news about James.”

“Sandra, I’ve had no news about James,” I replied.

There is probably no good way to tell someone that his brother has died, but there are bad ways. Poor Sandra was floored. “I’m so sorry, Karl. I can’t believe the police haven’t been in touch. James died of an overdose yesterday.”

I found myself spinning around my office, picking things up and putting them down, at a loss what to do. I headed home.

From the station, I called Sandra again. She had spoken to her colleagues and to James’s drug rehab clinic. My details were all over James’s records as next of kin. So were our mother’s. And Sandra had passed them on to the police officers who went to his flat after the 999 call.

Why had my brother’s body been in a north London morgue for 24 hours without his loved ones knowing?

The bare facts emerged slowly. A service user had come into the Grove drug treatment clinic and passed on the news they had heard on the street – that James had overdosed. The person who made the call to emergency services had bumped into two other drug users who had fled James’s flat when they realised he had overdosed. That’s what happens with drug addicts. Rather than risk getting drawn in, they walk away.

My concern was that the police, albeit 24 hours late, were going to turn up at our mum’s house in Norwich to break the news. So I made the most painful phone call of my life.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

We had feared this for more than 20 years of coping with James’s addiction, multiple overdoses and near-death experiences. My mother and I had even discussed it with James. We thought we had been preparing for this moment. It was only when it arrived, that we realised we hadn’t.

Mum was desperate to see her son, but she couldn’t until we could get his body to a funeral director’s

Mum was desperate to see her son, but she couldn’t until we could get his body to a funeral director’s

James’s body had been moved to the mortuary at Haringey coroner’s court. There’s no facility for anyone to view loved ones there. Mum was desperate to see her son, but she couldn’t until we could get his body to a funeral director’s. We immediately decided that James should go home to Norwich. He loved London, but Tottenham had been particularly cruel to him.

For days, I chased the police and eventually got through to the two officers who had found James. I asked why they hadn’t notified the next of kin. The first officer simply seemed to blame her colleague; she would speak to him. When I eventually tracked him down, he admitted that he’d forgotten: forgotten to tell the next of kin about the dead person that he had found. There’s no way on this planet that would have happened if James had been wearing a suit and been found in a flat in Canary Wharf. As a “junkie”, it appeared, he was a second-class citizen; he didn’t matter. We were told regularly how unusual it was for “someone in James’s position” to still have family members in their life.

Maybe the officers assumed no one could love someone like him. That no one loved my brother James.

James as a boy, surrounded by wrestling figurines.

The boy he was

James was my half-brother, although we only ever referred to each other as brothers. I was nine years older than him, and we grew up on a council estate on the outskirts of Norwich. James was a normal kid – mischievous and into WWF wrestling, skateboarding and, later, music. He could be difficult. He was a defiant child. He didn’t much like authority. Someone once said he had an inflated sense of injustice. That was true – nothing was ever really his fault, always someone else’s. But all in all, he was just a kid and then a pretty normal teenager.

In his early 20s, he was living an alternative lifestyle in squats and caravans. Music was still at the heart of everything he did. Along with that came a party scene, in particular, the illegal rave scene. He and his friends invested in a sound system. They were known as Molotov and they set up at raves and mini-festivals up and down the country, and as far away as the Czech Republic and Italy. What started out as recreational drug use became a habit. At a festival one Easter, James took too much liquid LSD and had a bad trip that lasted several days. It left him with what the doctors called drug-induced psychosis – auditory hallucinations and intrusive thoughts, mental health problems that would plague him for the rest of his life.

For the most part, we all loved taking drugs. It was fun… growing up on a council estate in the 90s, they were everywhere

For the most part, we all loved taking drugs. It was fun… growing up on a council estate in the 90s, they were everywhere

But this isn’t a Nancy Reagan “Just Say No” piece. We said “yes”. For the most part, we all loved taking drugs. It was fun. When we were growing up on a council estate in the 1990s, they were everywhere. Kids on the estate were trying everything from glue and gas-sniffing to cocaine. Every kid dabbled. Every kid smoked weed – and as the rave scene broke, took LSD, MDMA, ecstasy and ketamine, too. There were times when I took drugs with James.

But most of us kept a lid on things. I always hoped his increasing consumption was a passing phase and that he would be fine. I would reassure our mum that I’d been the same at his age, and here I was with a career and a family. He would come out the other end. I didn’t realise how much he had deteriorated.

It was the psychosis – the intrusive thoughts and voices – that ended up pushing James towards harder drugs. He told me later that someone suggested that heroin would stop the voices. He smoked it for the first time at 22, and it worked. It did an excellent job of stopping those voices. But they wouldn’t stay away. Between the highs, they came back.

Mum, guilt and the system

There’s a photograph of James and our mum that always stirs a sense of guilt in me. A young-looking James has his arm around our mum who is evidently going through treatment for breast cancer. There’s an addict’s hardness in my brother’s face in that photo that I don’t recognise. And his lifestyle was starting to have an impact on those closest to him.

James and his mum

Mum worked as a receptionist at the local NHS hospital and, from her modest salary, she was spending thousands to bail him out from drug debts. Threats of violence meant James was desperate to get hold of money any way he could. During those early years, my mum dealt with that alone.

Money, and the lack of it, had started to become a big problem in James’s life. One of his psychiatrists once invited me into the room during his consultation and shared his insights into the hard work of being an addict. It’s a 24-7 job.

You don’t finish. You don’t get to rest. Every hour of every day is consumed with where you get your next hit. It takes intelligence and resilience. Hearing this from the psychiatrist brought me up short. James was smart, and used to think constantly of ways to get money to get more drugs. The psychiatrist described James as a voracious drug user and drug seeker. The seeking had become all-consuming.

The heroin was everything. He was tied to the spoon and needle

The heroin was everything. He was tied to the spoon and needle

The comedown from heroin, which James was now injecting, drove him on. Prescription medication would help take off the edge; crack would wake him up enough to carry on the hustle. But the heroin was everything. He was tied to the spoon and needle. And the agony of the comedown can drive addicts to crime. James would say that in his circles, the girls were envied because “at least they could revert to prostitution if they really needed cash”. How can we accept a system where young women are forced into sex work to fund their habit?

James was 27 the first time he went to prison. I travelled home to Norwich to join our mum in court. In the dock, James looked a wreck. The judge described him, aptly, as a “hopeless addict”. He was a young man clearly out of his depth. He had been caught up in what the local newspaper called a “sting” – a police operation, no doubt costing hundreds of thousands of pounds, which led to a bunch of arrests. The local newspaper splashed its front page with photos of these supposed master criminals. The truth? The police had probably spent that money and hundreds of man-hours tracking down a handful of people at the very bottom of a very long chain. This wasn’t a success; it was picking up the dregs. James wasn’t a mastermind. He was someone scurrying around to get 20 quid for another couple of “bags of brown”.

James and Karl

Drug-free

The second time James went to prison, he was there long enough for it to be more than just a disruption. He used the time to try to kick the habit. He went on methadone, took some classes, and went to the gym.

Withdrawal was agony for him and painful for us. The worst part was watching his emotions return. Heroin clouds everything, keeps everything at bay. Lust, love – all those normal sensations – they’re gone, put on hold. And suddenly they come flooding back.

Guilt is the mean one. Guilt for borrowing money, guilt for lying, guilt for not taking care of people. James was unusual in that he never stole from our mum or me. For most addicts, stealing from loved ones seems to be par for the course.

When he came out of prison, he was drug-free. He was looking for a fresh start so he came to live with me and my family

When he came out of prison, he was drug-free. He was looking for a fresh start so he came to live with me and my family

When he came out of prison after 18 months, he was drug-free. He had even kicked the methadone substitute, which is as hard to quit as heroin. He was looking for a fresh start so he came to live with me and my family. I asked him to be best man at my wedding. I remember looking out into my garden, and seeing him bouncing on the trampoline with my sons. It was such a happy moment but I was holding back tears as I watched them all laughing. I was trying not to cry at the certainty that one day I was going to lose him.

London life

There’s an irony about moving to London to get away from drugs, from leafy Norwich to Tottenham. But James knew he couldn’t go back to Norwich. There would be too many connections, too many bad influences. So he wanted to go straight in London. He signed up for a college course, rented a flat, and got himself a cat, Sofia. Sofia was the love of his life.

James and his cat, Sofia

He was excited, but it didn’t last. By the time my wedding came round he had already slipped off the wagon. Within a few months he was on the slippery slope towards that phone call in my office.

With James living in London, I saw a lot more of him. I helped him to move house, repeatedly. There’s a bit of a cycle when you’re a junkie. You get offered some sort of temporary housing and put on a waiting list. Then, if you’re lucky, you end up with a council flat. But of course you ruin that, because you bring the wrong kind of people to it, upset the neighbours and make too much noise. You get evicted and finish up on the streets. The services might pick you up and get you back on a waiting list. And the cycle begins again.

For James, one of the biggest issues was the hoarding. He saw value in everything that he came across in a skip or a bin on the street. He was convinced that all those wires he had collected, the discarded laptops, and broken TVs, were worth something. He could sell them, make a few quid, hustle, earn some more, get some more gear. But, in truth, he just hoarded. So his flat ended up looking like something between a jumble sale, a mechanic’s yard, and an electrical store. Full of old, broken bits and pieces. No room to sit down, no room on the floor. Hoarding had taken over completely.

Occasionally, someone else would take over. They call it cuckooing: people take advantage of vulnerable individuals and turn their houses into crack dens for storing, selling and taking drugs. More often than not, the people selling heroin – mostly kids in their 20s “shotting” for gangsters further up the chain – never touch it. James was cuckooed twice. These visitors would keep him on a tight leash; he would get in touch and describe the worst kind of bullying. He might manage to get out of the house long enough to make a phone call to me, but never the police, because “grassing” would come with even worse consequences. My sense of impotence was intense. I would imagine kicking the door down and kicking these people out but, in truth, they were gangs with machetes, unlikely to be intimidated by a Guardian-reading HR director from Surrey. I often thought about paying someone to do the job for me.

I had a beautiful relationship with him. He was funny, warm and kind

I had a beautiful relationship with him. He was funny, warm and kind

Phone calls with James had always been a bit of a mixed blessing. I had a beautiful relationship with him. He was funny, warm and kind. But mostly when the phone rang I knew what it was for. Most likely, “Can I borrow 20 quid?” or “Can you do the code?” “The code” meant making a cash code so he could get money out of an ATM.

Brothers together

Sometimes I would rage that he made me feel like a cash machine. I would scream at him that we hadn’t heard from him since the last time he needed money. But there was always a “justifiable” reason. The electricity meter was empty, no food, vet fees for his cat, travel pass to get to an important appointment. I would try to explain to him that it was, in fact, always because of heroin. Very occasionally, he would be completely truthful and tell me that he needed the money because he was sick from withdrawal. I was so conflicted. I could afford the £20 that meant so much to him, and sometimes I gave it freely. On other occasions I would add up how much I had given him that week, month or year and throw it at him. It ran into thousands. Mum had given even more.

Mostly, I would give in. Regardless of how heated the call became, he would always follow up with a text that ended the way all his messages did: “Infinity love x me x”.

Most of the time he was penniless and hungry. James earned most of his money from begging on the street

Most of the time he was penniless and hungry. James earned most of his money from begging on the street

Even simply asking James “how are you?” was difficult because his life was unimaginably difficult. Most of the time he was penniless and hungry. James earned most of his money from begging on the street outside Seven Sisters tube station. With him, in an old pram, was his cat. She was unable to walk after an “accident”. James always suspected that she had been deliberately thrown out of a third-floor window during one of these cuckooing periods.

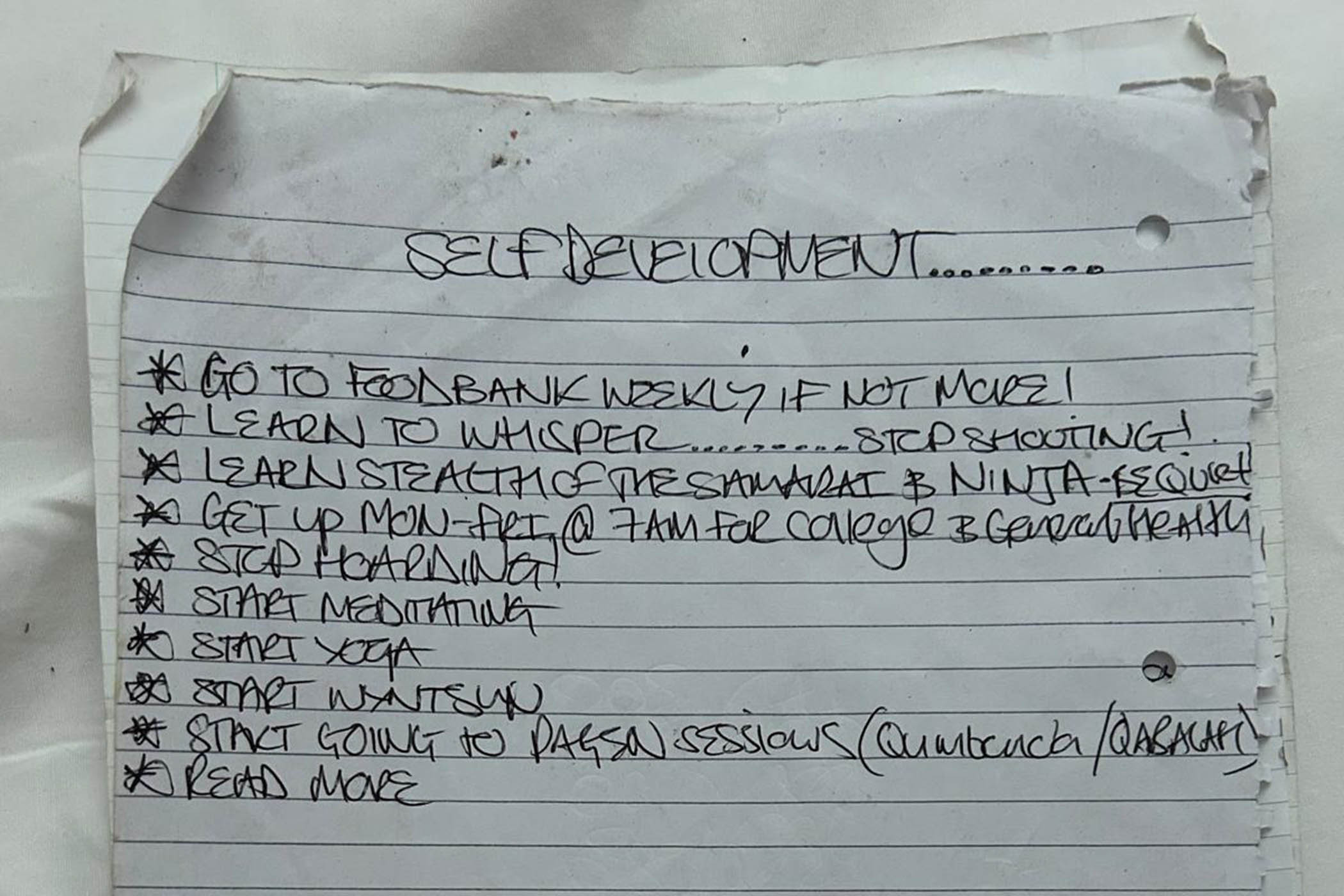

After James died I went to his flat and gathered up anything of sentimental value I could find. There was list after list after list: “To do” lists, “To get” lists, a “Self Development” list.

This was one of the lighter ones:

Go to food bank weekly if not more

Learn to whisper… stop shouting

Learn stealth of the samurai and ninja – be quiet

Get up Mon-Fri @ 7am for college and general health

Stop hoarding!

Start meditating

Start yoga

Read more

James’s ‘self development list’, found in his flat by his brother, Karl

The guilt and the fight

Well meaning people continue to tell me how he’s at peace now, no longer tormented. That’s rubbish. We lost James twice. Once to the addiction. And then we lost him again. And this wasn’t just some sad life that was no longer worth leading. We weren’t better off putting him out of his misery. He carried naloxone with him at all times to avoid overdose. He wanted to live. But because of the way his addiction is criminalised in this country, he was allowed to die.

There were 39,232 opioid-related deaths between 2011 and 2022

There were 39,232 opioid-related deaths between 2011 and 2022

For years, I had been quietly following the drug reform debate from the sidelines. But a couple of years ago, I stopped watching and became a trustee of the Transform Drug Policy Foundation and Anyone’s Child, charities that campaign for reform of our drug laws. Their work is driven by an uncomfortable truth: in England and Wales, there were 39,232 opioid-related deaths between 2011 and 2022.

And when you sit with that number, it’s hard not to think about the way we respond to other risks. Less than half as many people die on the roads in England and Wales and, quite rightly, there’s a whole infrastructure of prevention: speed cameras, compulsory seatbelts, 20mph zones, public-awareness campaigns. Why don’t we bring the same urgency or commitment to drug-related deaths?

If compassion and love aren’t reasons enough to act, if saving the life of someone like my brother isn’t enough, then simple economics should be. The money we waste criminalising people like James could fund proper treatment, housing and mental health care.

We already hand out methadone – why not the safer, controlled alternative: heroin itself?

We already hand out methadone – why not the safer, controlled alternative: heroin itself?

Legal regulation would undercut the gangs, virtually end shoplifting and save lives. We already hand out methadone – why not the safer, controlled alternative: heroin itself?

It’s not a popular view. I know most people would rather donate to a donkey sanctuary than fund a programme that keeps junkies alive.

But I’ve seen what happens when we look away. People die. My brother James died.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, you can call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 988, chat on 988lifeline.org, or text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org

Photographs supplied by the Elston family