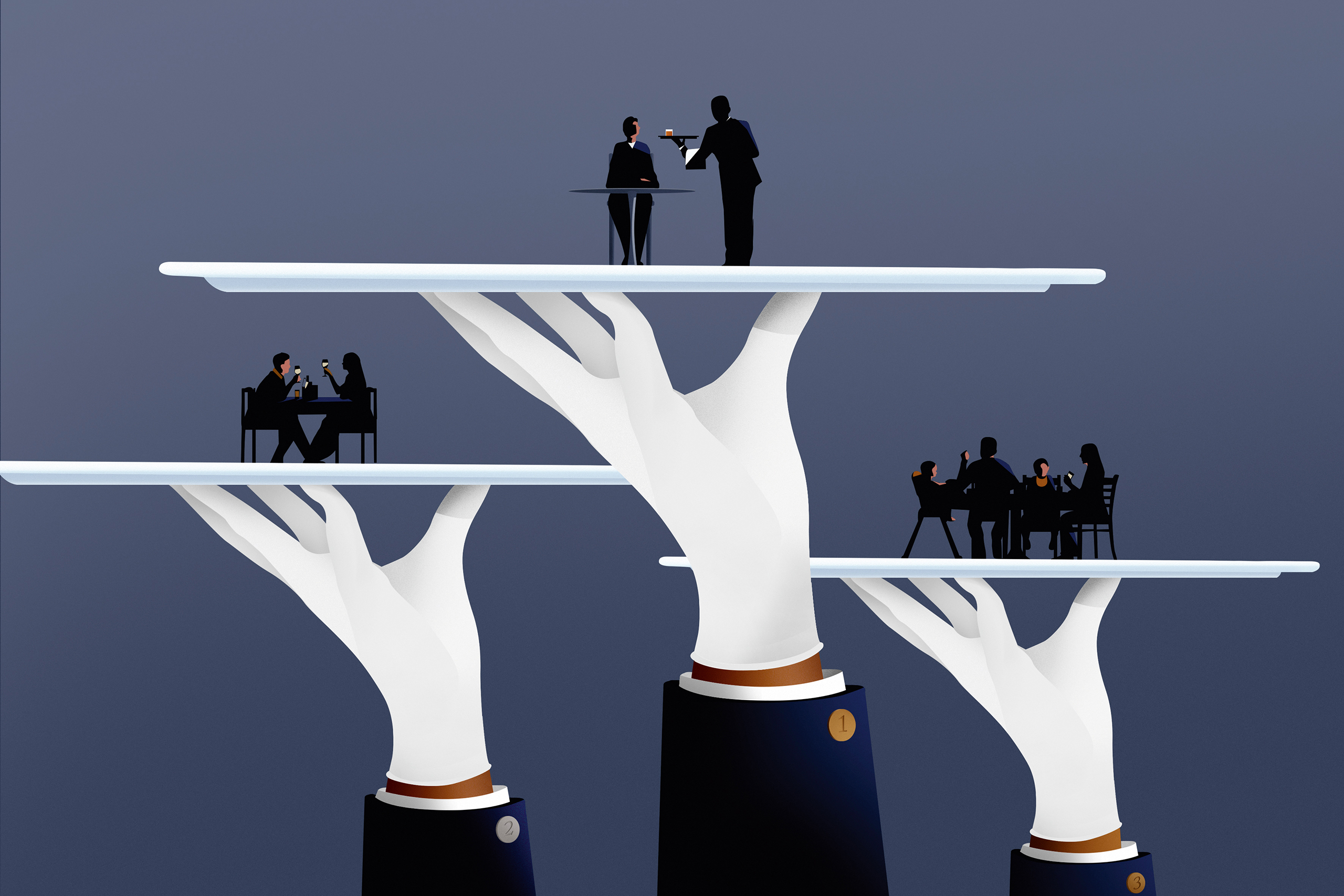

Illustrations by Matt Murphy

In money, time, brain space and enthusiasm, Observer readers put a lot of resources into eating out. But are we maximising that investment? We asked chefs, restaurateurs and critics how to get the most out of every meal. In 2025, this is how you win at restaurants.

Filter the food noise

We are bombarded with restaurant tips: TikTok, Instagram, booking apps, TV, print critics, Tripadvisor, friends, Google reviews, guidebooks. Research should operate on two levels. First, get an overview from dedicated sites such as – in London – Hot Dinners and London On The Inside. Then get granular by following foodies whose restaurant tastes overlap with yours (chefs, wine experts, suppliers), or explore niche interests by subscribing to a Substack, such as the business meeting-orientated Professional Lunch, whose London guide is also maintained as a Google Map.

In the US, and New York in particular, the Beli app’s supercharged word-of-mouth is causing a stir. Users can share detailed restaurant reviews in a map format, either publicly or in private social networks. Dubbed “Strava for restaurants” by the Telegraph, Beli includes leaderboards where hardcore users compete to contribute the most reviews. London is already among its top 10 “most active cities”.

Find deals on meals

Signing up to mailing lists may sound archaic, but, says Cardiff-based hospitality consultant Jane Cook, restaurants reward loyal diners with “subscriber-only perks like launch discounts or the occasional promo code”. Follow restaurants on Instagram for similar notice of “quiet night deals – think Tuesday set menus – and, with newer restaurants, short-term discounts to drive early footfall”, she says.

In London, softlaunchlondon.com aggregates deals during “soft launch” periods, when menu prices may be slashed by up to 50%. Do not overlook old reliables such as pre-theatre menus, says Rochelle Cohen, founder of PR agency Roche Communications, or set lunches (“often incredible value”) and opportunities for cut-price corkage.

Get the hot table

Each service is so dynamic (cancellations, late arrivals, tables held for walk-ins), that, as David Carter, owner of London’s Oma, puts it, “fully booked hardly exists”.

Exploit that by phoning an hour before service, or visiting outside peak hours (3-5pm if open all day; 9pm during an evening service), and try your luck. “See if they can squeeze you in on a shorter turn,” says James Snowdon, co-founder of the Palmerston in Edinburgh. In 2012, that tactic got Snowdon a table at London’s hottest ticket at the time, Dabbous.

Related articles:

Beat the rush

“Set alerts for your favourite critics, as reviews often go online before print,” says Tonic PR founder, Frances Cottrell-Duffield. Book the hits “that day, ahead of the hordes”. Or …

Swerve new openings

Social media encourages the thirst to be first. But pros give restaurants time to bed in. For example, The Good Food Guide waits three to six months before inspecting. “The first weeks are tough. I try to give it a month – long enough to get the kinks worked out,” says critic Andy Hayler, who has reviewed 169 restaurants with three Michelin stars.

Avoid busy services

The hospitality cliche is that everyone wants a table at 7.30pm on Saturday night. Few experts do. Generally, they avoid the busiest times and special occasions like Mother’s Day, when kitchens and waiting staff can become stretched, preferring calmer slots and midweek.

“I feel restaurants are best at the beginning of service, which seems to be the way bookings are going – everybody wants to eat earlier – or at lunch,” says critic Jimi Famurewa.

Eat for joy, not kudos

“I do think a lot of people are going to restaurants now for content,” says London food PR Hugh Smithson-Wright. He relays tales, from industry friends, of very-online diners visiting hip venues to be photographed in situ but, at times, not even finishing the (viral) dishes they order.

At his Manchester restaurant Madre, chef Sam Grainger watched a table of diners take photographs for 17 minutes before they ate anything. Seeing them focus more on being in the cool restaurant, and documenting that, than on the food “made me want to cry”, he says.

Smithson-Wright describes a “mapification” of eating out, where diners work through lists of “hot” venues – at worst as “a tick-box exercise”. His approach is very different: “Know what you like. Seek it out. Don’t let others tell you. You will have a 10 times better time.”

Become a regular

We crave newness. But in 2024, The Good Food Guide had 60,000 votes for its Best Local Restaurant award, emphasising the value of a favourite place where the staff know your name, can always find you a table and know how you like your negroni.

Beware photogenic dishes

Dishes designed to have the wow factor on Instagram do not always deliver deliciousness, warns Time Out London’s food and drink editor Leonie Cooper. Be cautious about dishes that are hyped online but have little “comment on flavour”.

Feed kids first

“Specify that children should get their food first,” says Jacob Kenedy, chef patron of London’s Bocca di Lupo. Making sure hungry kids eat as soon as possible creates a “much better energy”.

Embrace solo dining

“Staff often seem to warm more to single diners,” observes Stefan Chomka, editor of industry website restaurantonline.co.uk.

George Colebrook, of private dining company Arete, agrees. Last year he treated himself to lunch at Quo Vadis in London and “felt like a king”. “Servers respect a solo diner. The decision implies a strong desire to focus on the experience, the food, the drink.”

Do your due diligence

“We’ve had people come to Bank who don’t like smoky food. It’s all cooked over fire,” says Dan O’Regan, co-owner of the Bristol restaurant. In Glasgow, Celentano’s co-owner Anna Parker reports a minority mistaking its Michelin Bib Gourmand for a Michelin star “and expecting a fine dining experience”.

If, as the diner, you do not engage with the basic premise of the restaurant you are visiting, says O’Regan, “you’re setting yourself up for failure”.

Respect the booking

Restaurants are businesses “with frightening overheads”, says Chitra Ramaswamy, restaurant critic for The Times in Scotland. They are not magical “emporiums of desire fulfilment”.

Remember that. Because blithely turning up late for a 1hr 45min booking, particularly with the wrong number of guests, gums up a service that’s carefully planned to allow each table time to eat at a sensible pace, but which also enables the restaurant to turn a profit. Late arrivals feel rushed out when the next party arrives. For staff, it creates awkward friction. Everyone loses.

Never dine in a bad mood

Restaurants are “live theatre”, says Robbie Bargh, founder of the Gorgeous Group hospitality consultancy. Diners are the audience, staff performers. Sullen guests spoil the show. “You’re not some passive recipient of the food,” agrees Ramaswamy. “You’re helping create the atmosphere in that restaurant.”

Build a rapport with the staff

“When they ask, ‘How are you?’ I ask how they are, too. Which, nine times out of 10, surprises them,” says Jules Pearson, London hotel group Ennismore’s VP of restaurant development. That greeting “sets the tone that you’re sound and it’s going to be a two-way relationship”.

“Come curious, ask questions, show you’ve done your research, ask for recommendations, smile, say please and thank you,” says Rochelle Cohen.

Sit at the bar or counter

It is visual theatre. Enthusiastic interaction with the chefs may even yield memorable extras – tastes of exciting new ingredients, wines or dishes in development.

Ask the staff, not your phone, if there is a dish or ingredient you don’t recognise, staff are eager to share their knowledge – and, says Bargh, they can unlock the “secret golden eggs” (an obscure drink that staff love, a chefs-only version of a dish) that can transform a meal. “I want to build a quick, sincere relationship with my server. That’s important.”

“I always ask the waiter what’s the most delicious thing on the menu,” says Cooper. If they have not eaten from it, “consider this a red flag”. Good restaurants hold regular staff tastings “so they can talk about the menu with authority”.

Freestyle the menu

“Don’t be afraid to write your own rules,” says Chomka, who, rather than starter-main-dessert, will go “big on starters and dessert”, if that offers tastier variety.

“As a vegan, I’ve been doing my own version of small plates for years,” says Meriel Armitage, owner of London’s Club Mexicana restaurants. Sometimes a selection of vegetable starters or sides might “pack more zing” than a main.

Don’t play restaurant critic

“Today, there are too many people whose sole motivation is to eat in the hottest new places, then write a review,” says Charlie Sims, co-owner of London’s Sune. This encourages a hyper-analysis – “trying to pick holes” – which inhibits natural enjoyment.

Learn how to complain

Be polite, specific and objective. Disliking a competently made sauce is subjective. A 50-minute wait for your main is an obvious error. In busy venues, offering to email the manager may elicit the best response (a free meal, potentially). There is no need for “confrontation”, says Bargh, but problems should be raised. “If it’s not been great and you’ve not complained, more fool you.”

Not feeling it? Walk away

If you enter a restaurant as a walk-in and you’re ignored, staff are fraught and the vibe is chaotic, says Bargh: “Walk out. Absolutely.”

Master small and sharing plate menus

No one wants to speed-eat from a table crammed with dishes. Order in stages, and ignore recommendations about how many dishes you need. It’s “a way to bump the bill up”, warns Liz Carter, The Good Food Guide editor-at-large. Instead, choose a couple each. You can order more, later. Be disciplined, to control the cost.

Be realistic

“If I’m eating somewhere I think might not be great,” says chef and restaurateur Tommy Banks, “I order something they’ll get right. Not the soufflé. Generally, pizza is always quite good.”

Eat something you wouldn’t eat at home

In 2025, prized luxury ingredients (oysters, lobster, hand-dived scallops, caviar etc), and the finest prime proteins, such as cod and beef, can be ordered online by anyone who can afford them, and YouTube tutorials will teach you how to nail the perfect steak. For capable cooks, therefore, it is more cost-effective to eat such items at home, rather than pay restaurant prices.

Conversely, at the cheaper end of the menu there are dishes – what Famurewa calls “low-lift mainstays” – that are so simple to execute, such as padron peppers or dressed burrata, that it can seem a waste to order them when you have a skilled professional kitchen working to feed you.

To get the best value from a menu, choose dishes with ingredients that are more fiddly (offal, for example), slow-cooked (beef shin), or less exalted (sardines), which you might not faff about with at home or do not have the ingenuity to make shine. Kitchens that source whole fish (or whole animal carcasses) will monetise the trim in fish cakes, fish pies or fritters, perhaps served on the lunch menu. These cheaper dishes, argues Alex Rushmer, chef-owner at Cambridge’s Vanderlyle, represent better value than, for example, a dish that revolves around a tightly portioned section of expensive cod loin.

You are spending “a greater proportion” per dish on “the imagination, experience and effort” of the chefs to transform that trim into something tasty, rather than paying a premium for a particular cut of fish.

Look for the curveballs

Game dishes, offal, a paté, a less popular fish such as coley or pollock – such dishes are often “slightly underpriced” to ensure they sell, says Rushmer. What’s more, they “are usually the dishes that the chef feels strongly about”, having had to argue to get them on the menu. Such dishes may be new to you – but, says Colebrook, “Mystery plays a large part in the quest for joy.” Trust your waiter. Give it a go.

Don’t be fobbed off with a substandard dessert

For complex reasons, says Carter, restaurant “desserts” now often consist of “chocolate mousse, ice-cream with bits” and other easily prepped, quick-service options. “You walk away from that,” says Carter, and enjoy skilful pastry work at a local artisan bakery “for a fraction of the price”.

‘Don’t ask for dry white wine. Be specific and use words like ‘citrus, aromatic, mineral, rich’

‘Don’t ask for dry white wine. Be specific and use words like ‘citrus, aromatic, mineral, rich’

Jacob Kenedy

Be specific about wine

“Don’t ask for dry white wine,” suggests Jacob Kenedy. Most white wines are. Instead, use specific words like “citrus, aromatic, mineral, rich”. Talking about wine can be embarrassing. But a basic grasp of this code will “return untold value in things you love to drink”.

Challenge your sommelier

Be honest about what you want to spend. If you like chablis but cannot afford it, ask for alternatives, such as “unoaked chardonnay from another moderately cold place, like Bulgaria”, suggests Sunny Hodge, owner of London wine bar Aspen & Meursault.

Sommeliers relish such tests: “What’s the use of all that training if we can’t apply it to fun challenges?”

Question pairing suggestions

Don’t like white wine? Say so. Good sommeliers will have red or rosé alternatives. “Wine matching should enhance your meal, not dictate it,” says Klearhos Kanellakis, head sommelier at London’s Ekstedt at the Yard.

For best value, drink beyond big names, regions and grapes: “Hungarian dry Furmint, Greek whites, Austrian grüner veltliner,” suggests Kanellakis. At the same price point, he says, wines from Rioja, Tuscany and the Rhône “tend to offer far more for your money than Bordeaux or Burgundy”.

Even within Burgundy, says Charlie Stein, head of wine at Rick Stein Restaurants, there are “lesser-known appellations” (licensed growing areas) – such as Saint-Romain, Saint-Véran and Pouilly-Fuissé – that deliver “classic Burgundian character” without the sometimes “eye-watering” prices.

Alternatively, try white wines made not with chardonnay, but with Burgundy’s other grape, aligoté.

Don’t be afraid to take notes

Finally, making notes about the meal, mood and service will not only remind you about the experience but can also help “build a more thoughtful relationship” with the restaurants you love, says Emma Hemy, restaurant manager at Edinburgh’s Number One at the Balmoral.

She has met guests who take notes on each meal: “Favourite dish, new wine tried, something learned.” Give it a try.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy